Review

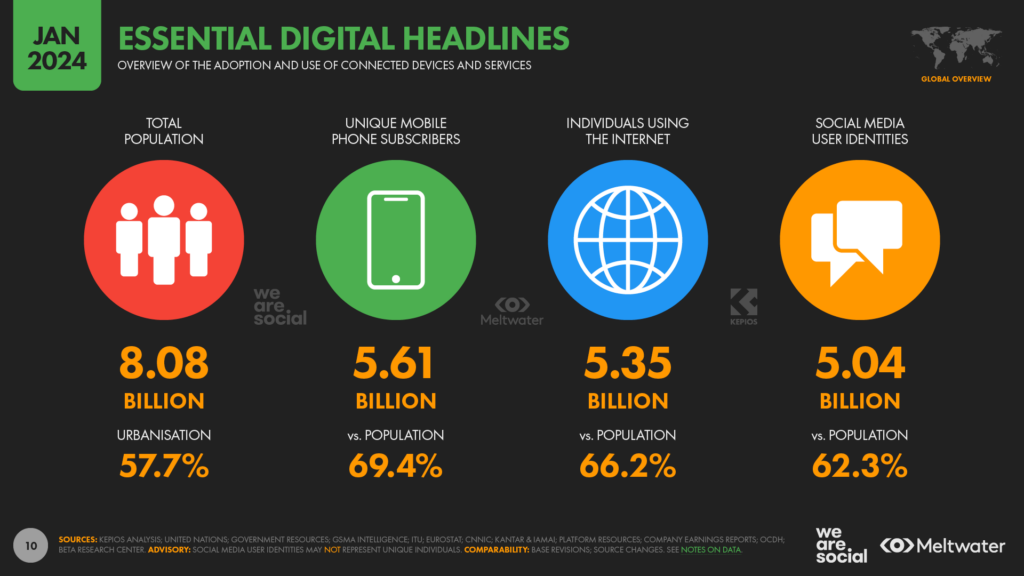

Digital technology has changed how historians research, write, and publish stories. These technologies are making local history more accessible by providing opportunities for community collaboration and engagement.

Digital storytelling is a communication technique that utilizes various forms of multimedia to create a compelling narrative. An easy and accessible way to share historical content.

Case Study

Other Examples

- Mapping the Civil War in Arlington

- Maywood

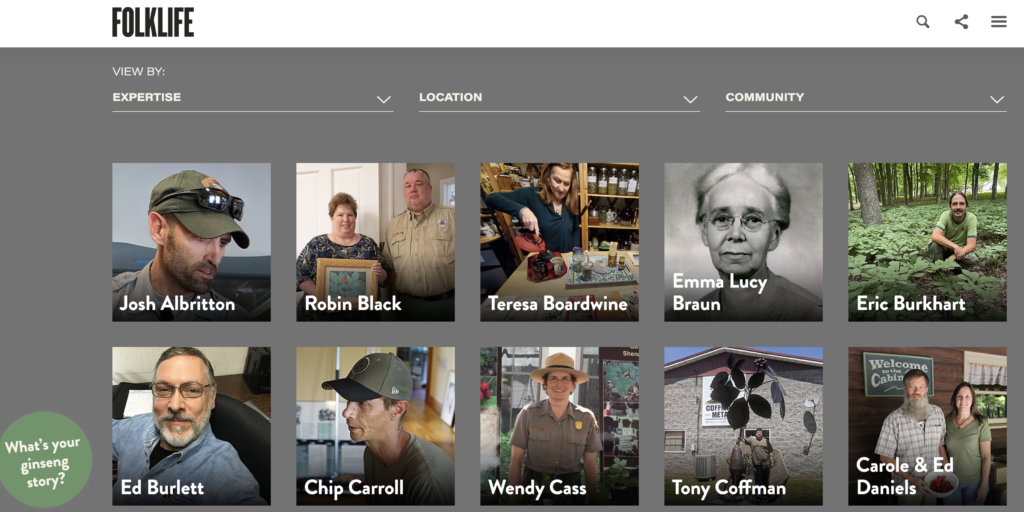

- Hurley Mountain Storieshttp://folklife.si.edu/american-ginseng

Definition

Digital history is an approach to examining and representing the past using information technologies. It draws on databases, hypertextualization, and networks, to create and share historical knowledge.”

Digital storytelling is a communication technique that utilizes various forms of multimedia to create a compelling narrative. An easy and accessible way to share historical content.

Changing the way historians “argue history”

Digital history is an approach to examining and representing the past using information technologies. It uses databases, hypertextualization, and networks to create and share historical knowledge.

Democratizing History

Arlington Historical is a free mobile app that puts Arlington, Virginia’s history at your fingertips. Find interesting stories about people, places, and events in Arlington history, and enjoy curated historical tours. Each point on the interactive location-enabled map includes historical information about the site along with historical images. Arlington Historical is a collaborative project with stories published by local historians, community members, and other history-focused organizations.

Survey of Digital Platforms & Tools

Online Platforms

- https://knightlab.northwestern.edu/projects/#storytelling

- mtcwia.com/timeline

- https://shorthand.com/the-craft/an-introduction-to-scrollytelling/index.html

- https://venngage.com/

- Scripto

- https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis/products/arcgis-online/capabilities/make-maps

- https://knightlab.northwestern.edu/projects/#storytelling

- BBC – The Catch

Case Studies

Tools

- https://voyant-tools.org

- https://kepler.gl/

- Paraphrasing and Summarizing Tool

- Scripto

- https://venngage.com/

- https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis/products/arcgis-online/capabilities/make-maps

- https://www.datawrapper.de/

- https://www.mapbox.com/maps

Case Study – Google

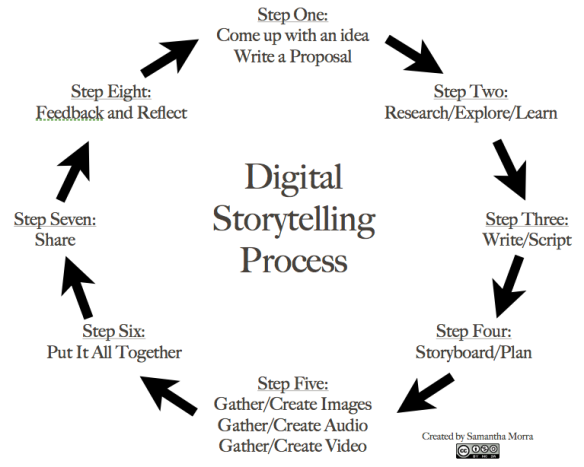

Digital Storytelling Process

Case Study

Research Tools

- https://archive.org/

- https://www.jstor.org/

- Library of Congress

- National Archives

- https://www.newspapers.com/

- Google Scholar

- https://www.davidrumsey.com/home

- https://www.gutenberg.org/

- https://library.arlingtonva.us/center-for-local-history/

- New York Public Library

- https://www.fairfaxcounty.gov/library/local-history

Writing for History

What are the Six Essentials of Digital Storytelling?

First-person Pronouns. Using these pronouns will make the message more authentic. We, us, our, and ourselves are all first-person pronouns. Specifically, they are plural first-person pronouns. Singular first-person pronouns include I, me, my, mine, and myself.

Dramatic Questions. Ask a dramatic question and try to resolve it by the end of the storytelling.

Emotional Stories. Design your story in a way that evokes emotion in the audience.

Condensed Stories. Make your stories as condensed as you can so that the audience can look at them in one sitting.

Remove Unnecessary Details. Pace your story in a way that makes the most sense and remove all the unnecessary details.

Use Your Own Voice. Narrate your story in your voice to elevate the impact of the message.

Digital History and Argument

Historical interpretation depends on creating and connecting persuasive accounts of the past into a framework of understanding. This is accomplished by selecting sources that can answer a research question, and identify those that provide relevant evidence. The basis of that selection can be their judgement of the truthfulness of a source, its aesthetic qualities, its representativeness, or its uniqueness.

Selecting sources requires that historians synthesize them to find patterns and structures, which guides how they arrange those sources into an argument, narrative, or interpretation which is the composite of the sources and not merely a retelling of any one of them. Historians may elect to arrange sources chronologically, geographically, topically, or along any other axis that reveals causation, experience, or consequences. Arrangement along those axes is part and parcel of contextualization, which might also be called comparison. The most basic form of historical contextualization is to understand a source by comparing it to other sources from the same period, place, or topic.

How does one write a Historical Argument?

A historical argument explains how or why an event occurred in the past. The argument is presented by a thesis statement, which must be specific, proven, and argued. The thesis statement is the main argument of the story and is supported by quality, relevant, and credible evidence to make a strong argument.

The components of a historical argument are:

- The thesis (specific, provable, arguable),

- The evidence (the information provided that supports the thesis statement), and

- The conclusion (the decision or deduction rendered that clarifies the position of the thesis).

- Other factors include previous arguments made by other historical scholars, how this particular piece of history impacts the understanding of the past or the present, and what processes and sources were used to come to any conclusions.

Project Review

Case Study