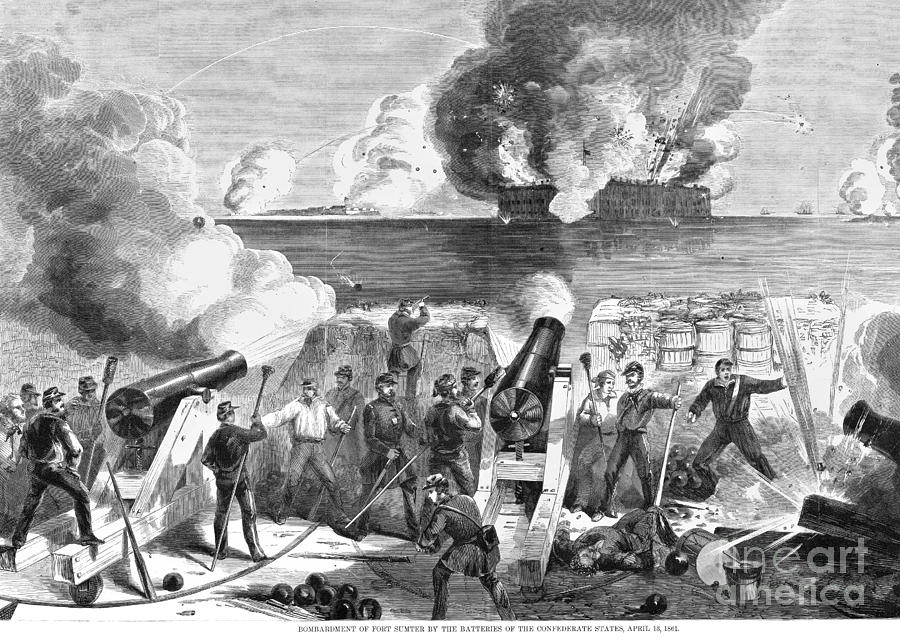

April 12, 2021 marks the 16oth anniversary of the start of the American Civil War. For many the conflict is long forgotten. But recent political events in Washington, DC have renewed interest in the war’s origins. It also serves as a reminder that sometimes people need to rediscover their history.

For the past semester, I have been taking a graduate course at George Mason University on Digital Public History. The course examines the impact of technologies, like the Internet, cloud hosted applications, and social media, on the public’s access to historical knowledge. For centuries, history was an academic process, based on scholarly research, and publications. However today, advances in information technology provide both opportunities and challenges as to how history is curated and publicly promoted.

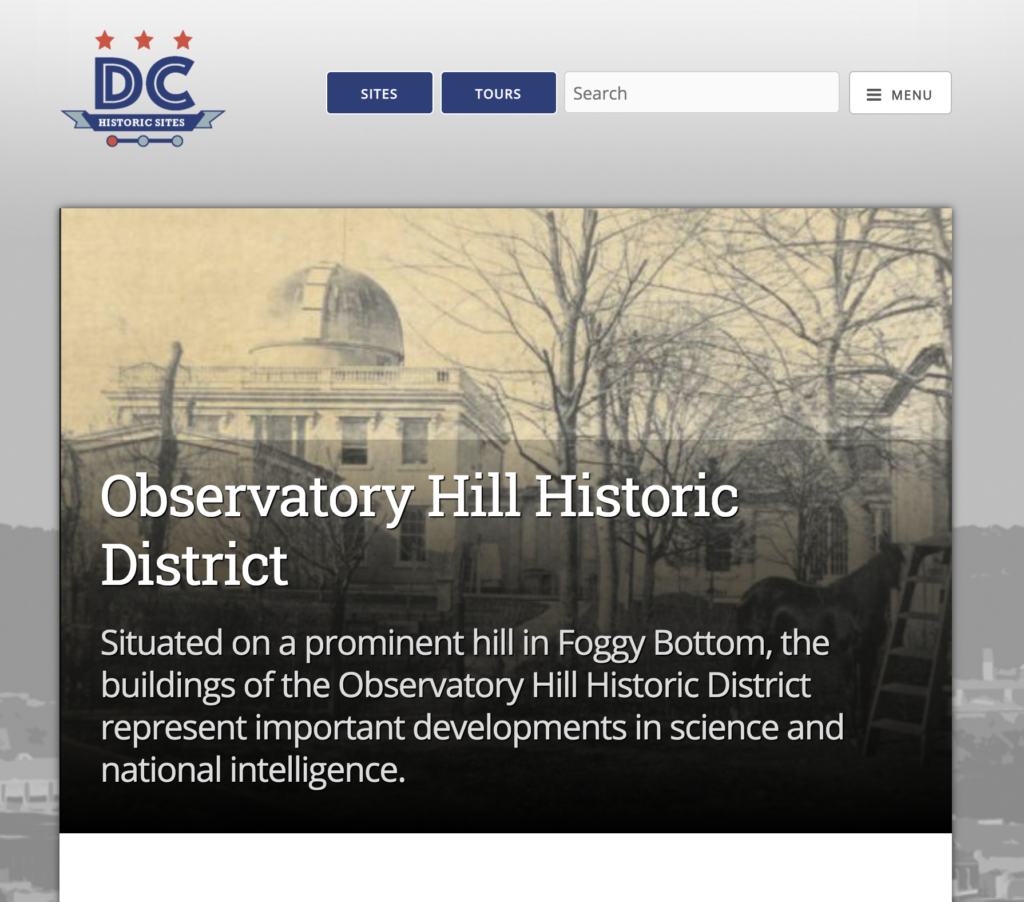

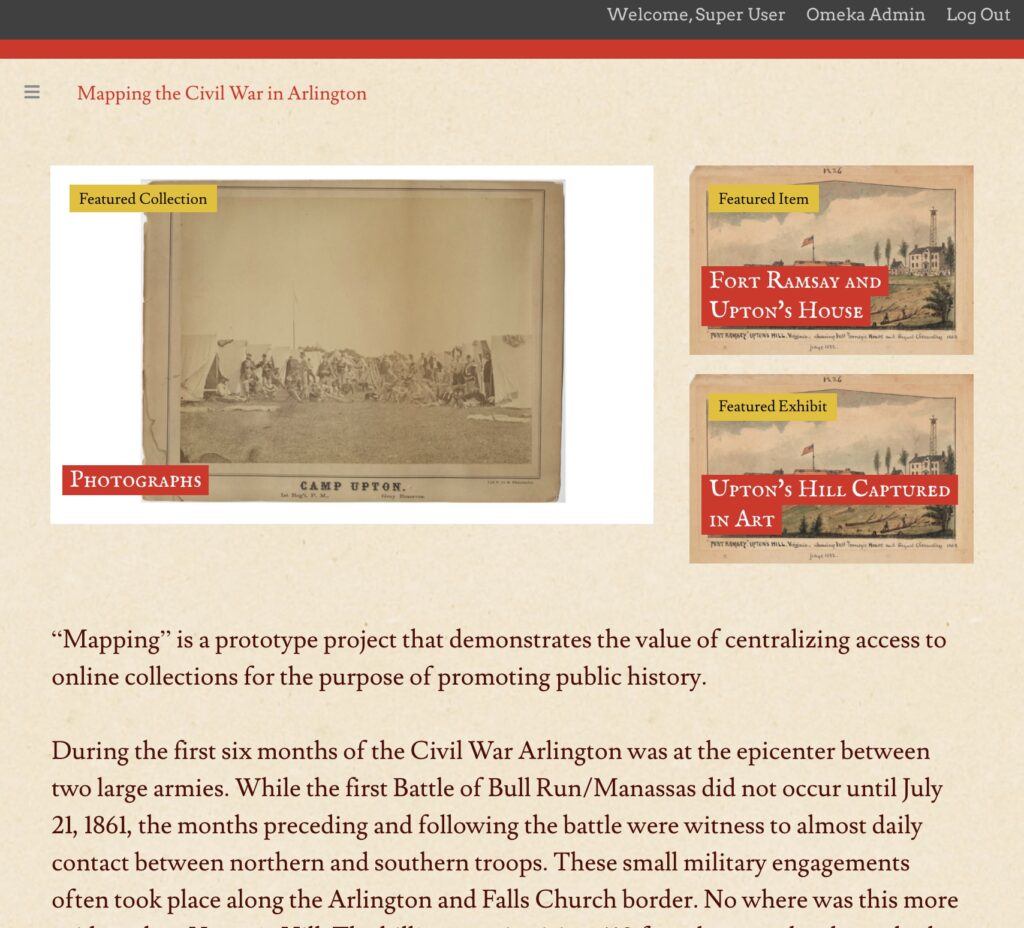

An important part of the course was to prepare a final project to demonstrate how to design and implement an online historical collection. For my project, MTCWIA.COM, I chose to focus on Civil War history in Arlington, Virginia. My argument or business case, is that people living in Arlington today are unaware of what happened literally in their backyards over 160 years ago.

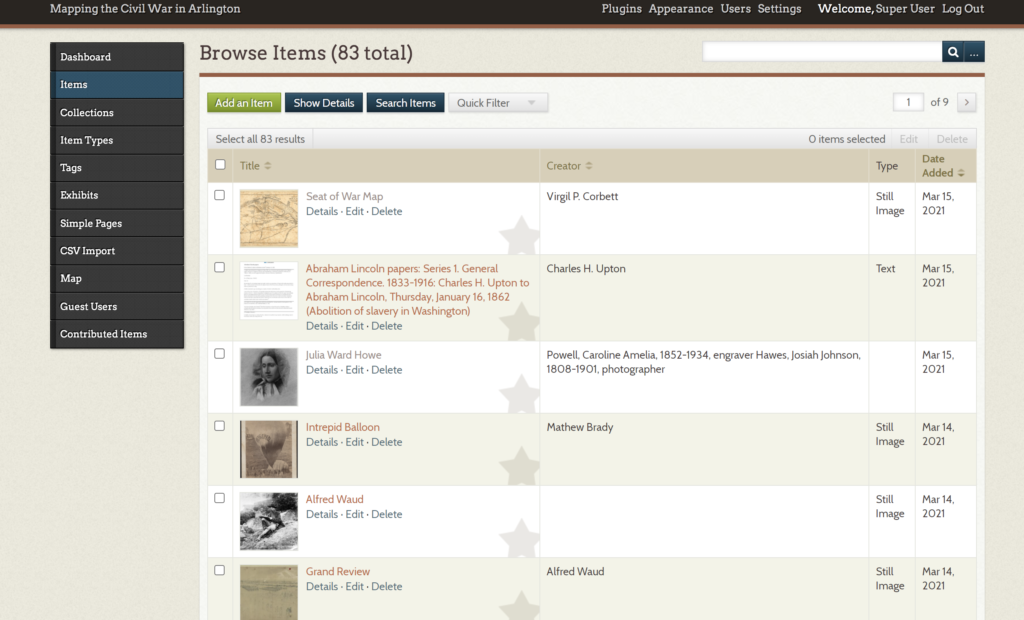

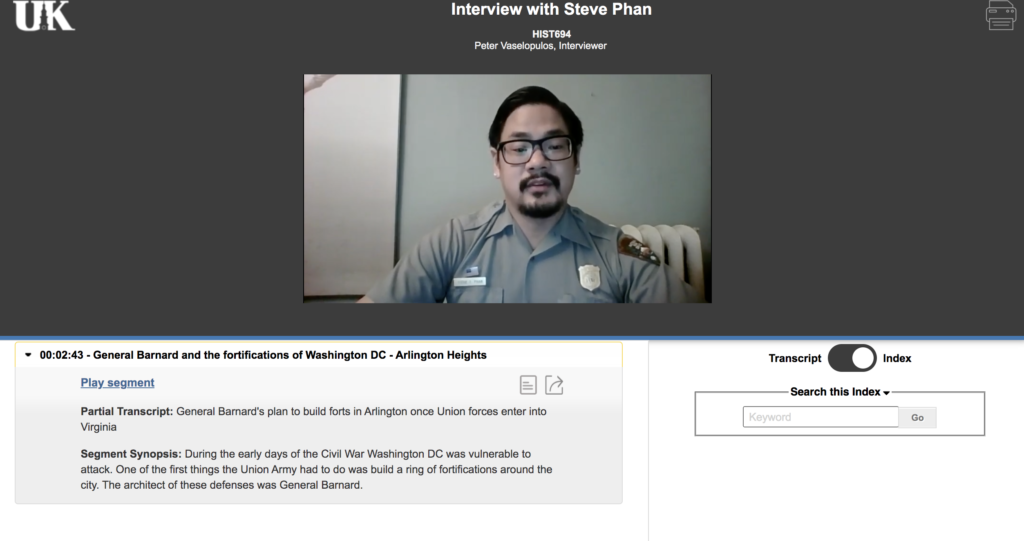

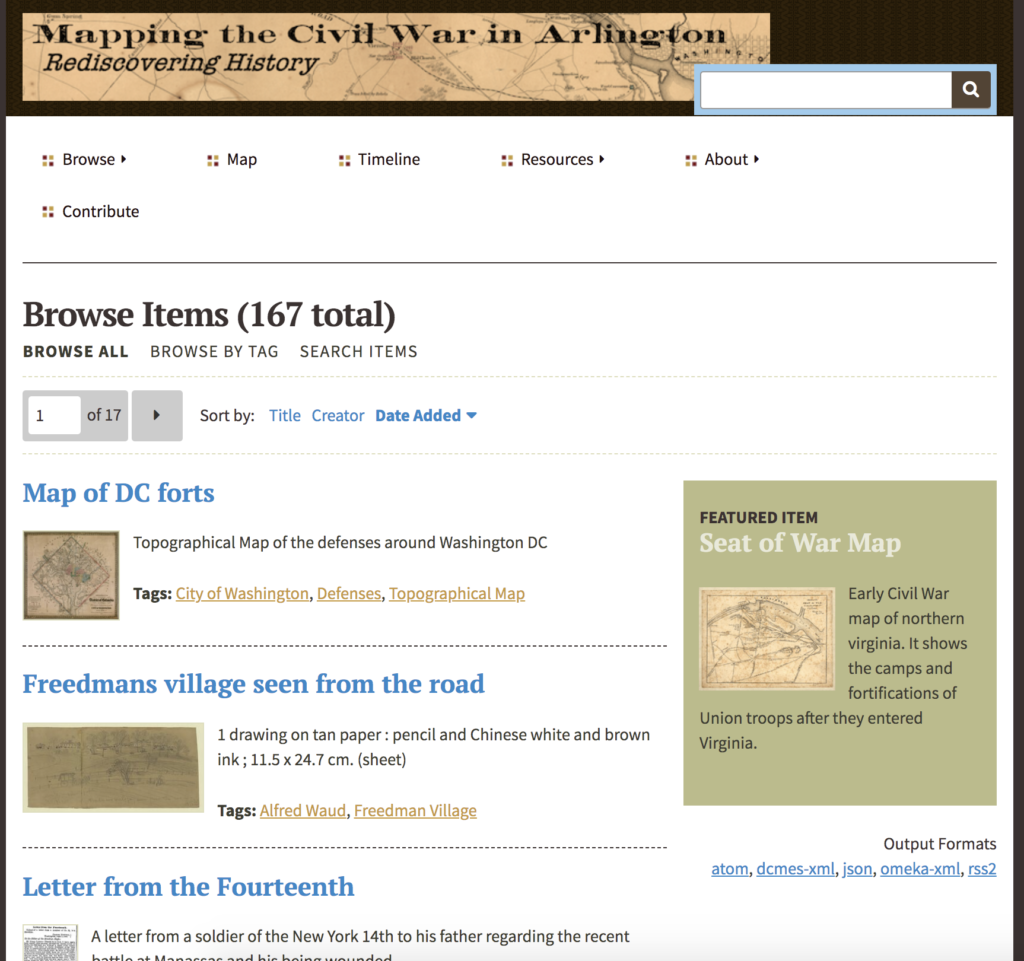

“Mapping the Civil War in Arlington” provides local historians, teachers and students, online access to historical photographs, drawings, maps, letters, newspapers, and official documents. These Civil War era primary sources promote a more collaborative interpretation of Arlington’s role during the conflict. “Mapping” also encourages new research and discoveries that will highlight the social, political, and cultural history of the people living in Arlington during the war.

For decades, Arlington’s Civil War history has been overshadowed by Confederate General Robert E. Lee, Arlington House and Arlington Cemetery. In fact, people in Arlington are surprised to learn about the numerous military engagements that took place during the war. Many are unaware of Arlington’s role in the creation of the Union’s Army of the Potomac. The challenge of “Mapping” was to make accessible a sufficient number of primary sources to support the case that a lot did happen in and around Arlington.

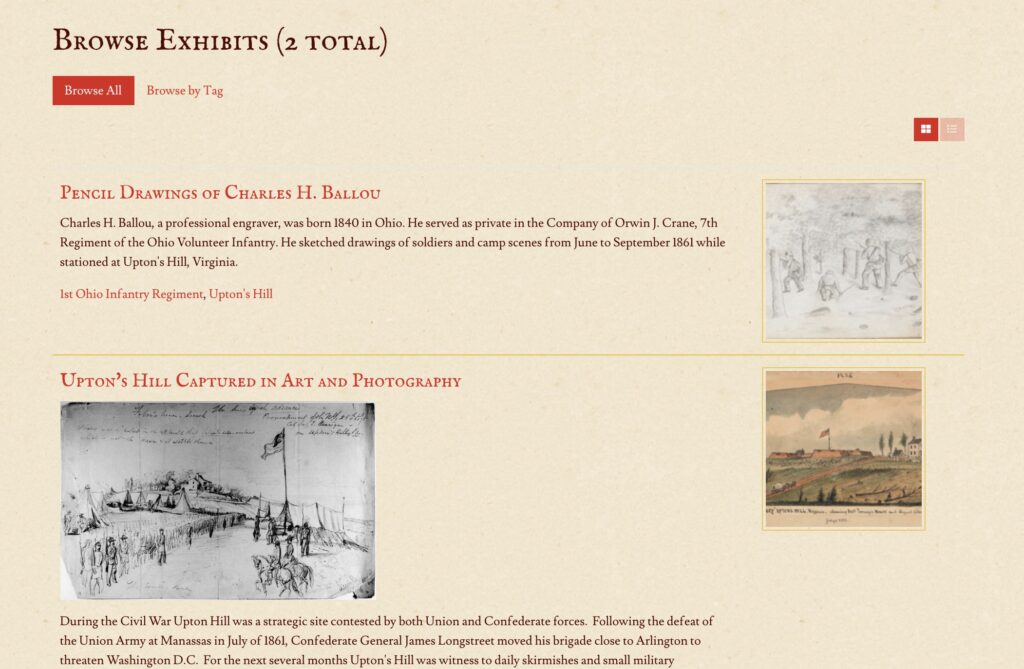

A survey of well known Civil War online collections, including historic newspapers, photographic collections, drawings, and diaries, revealed a wealth of publicly available primary source material. An important goal of the project was to curate some of this material and make it discoverable, especially, for local teachers and students studying the Civil War.

Since “Mapping’s” launch, user feedback has been very positive. Local historians like the site’s ability to centralize access to primary sources. This capability has already promoted new perspectives on what Union and Confederate forces were doing in around Arlington.

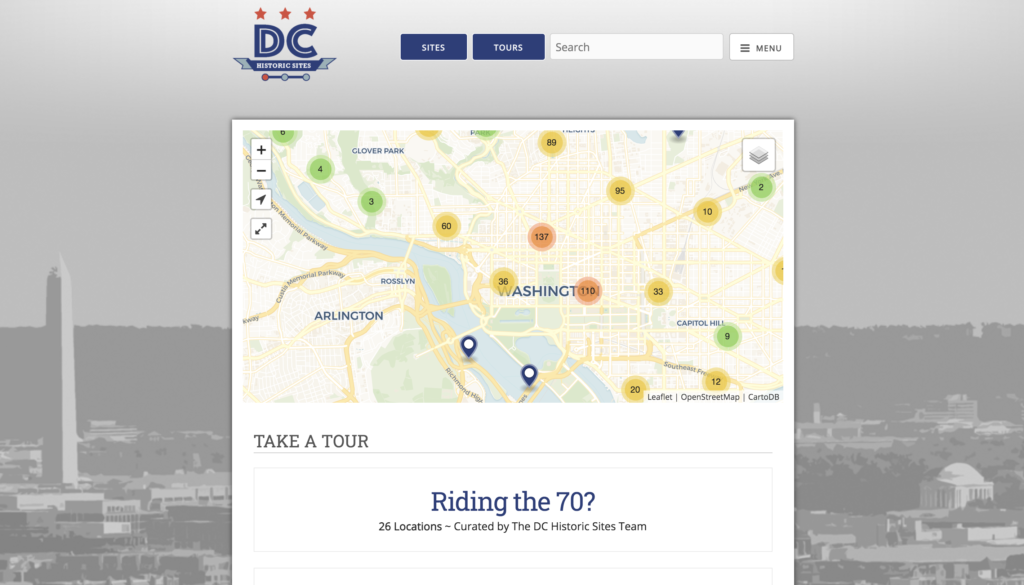

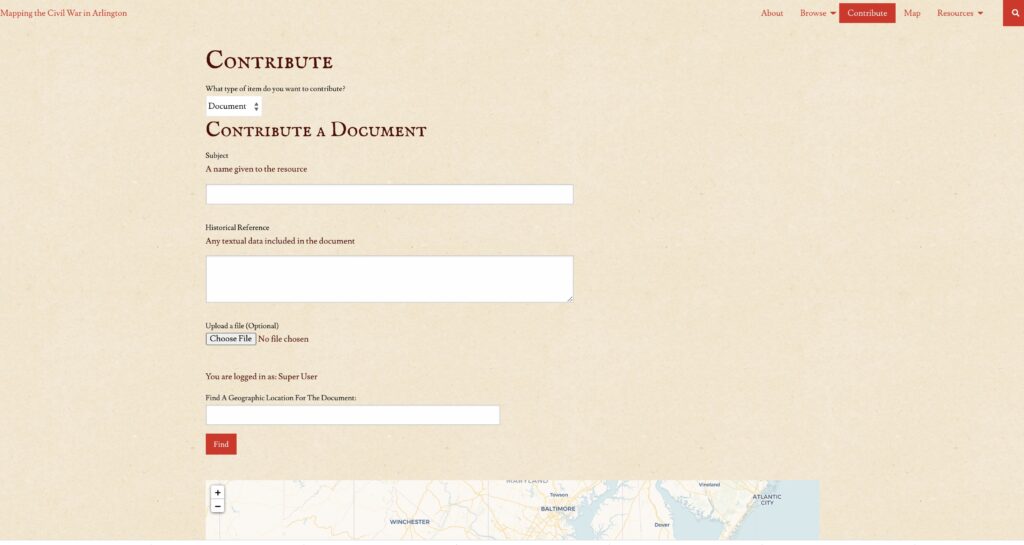

The hosted platform supporting the site is George Mason University’s Omeka. It is Dublin Core compatible, and the key design elements follow a traditional museum motif, including (items, collections, and exhibits). Some of the key features of the project are a mapping functionality that provides visitors the ability to identify their location in Arlington and historic events that occured close by. The site also includes a useful timeline feature that identifies some of the major historic events impacting Arlington. Finally, the site provides a collaboration feature that permits users to submit historic resources for review and possible curation.

Lessons Learned

Curating historical knowledge is both a subjective and objective process. Individuals studying history learn from a variety of resources, and are often influenced by different historical interpretations. In regard to digital public history, making primary source material available is the key to maintaining objectivity. The goal of “Mapping” is to demonstrate that people can “rediscover” their history when provided online access to previously “unknown” primary sources.

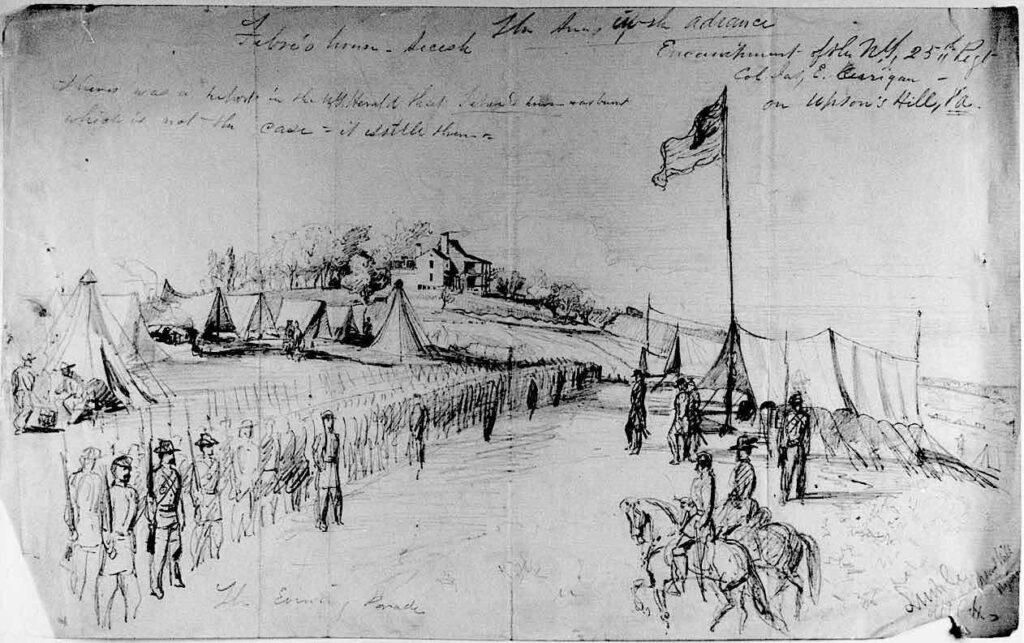

For years, many local historians claimed that not much happened militarily in Arlington during the Civil War. But in fact, a rather brief online research revealed that well over 50 regiments camped on Arlington’s Upton Hill during the war. That is almost the equivalent of over 35,000 troops. In addition, a review of historic newspaper accounts, and official records, has determined that dozens of military engagements occured in Arlington during the late summer and fall of 1861, resulting in hundreds of casualties. Newspaper accounts of the day called it the “Battle of Munson Hill.” For a while the threat of a major military engagement occuring in Arlington was real. While these historical resources have existed for almost 160 years, it was their rediscovery online that is encouraging a new interpretation of the local history.

One of the key lesson learned is that the success of a public history project is dependent upon its accessibility and discoverability. That means that an online collection must invest in the necessary time to properly document its metadata. This especially includes the necessary text associated with a newspaper article or diary. If the digital text is not provided along with the images of the article, then the “discovery” part is minimized. Public historians can not expect their audiences to read everything. It is in the searching functionality, that real discovery and historical associations can be determined.

Like traditional museum collections, public history sites still require some interpretation. This is especially important in trying to engage audiences and making sure the content is relevant. The Omeka platform’s exhibit feature permits some historical context to be displayed so audiences have a reference point. However, the primary value of a collection site, is its ability to catalog and index a wide variety of items, including images, text, and media. This is becoming a powerful resource for public historians, as they continue to help their audiences to rediscover history.