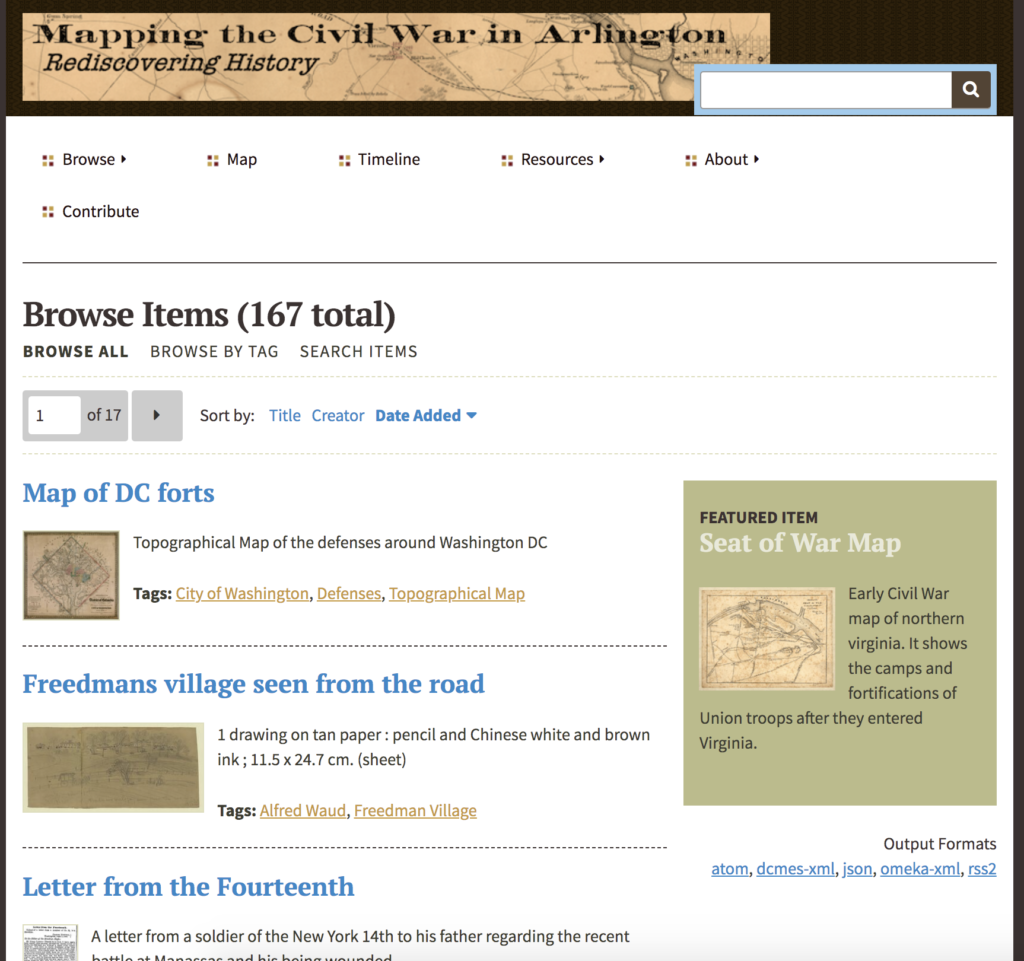

During the past week I have really enjoyed the readings on how to analyze historic photographs. It has helped me to refocus my final teaching history project. In addition I had the opportunity recently to interview a retired Arlington teacher. She was involved in standardizing county history curriculums, especially teaching the Civil War. I had her review my site “Mapping the Civil War in Arlington.” We discussed how a local history project could help Arlington teachers encourage their students to learn more about Civil War history. She expressed regret that “Mapping” was not available years earlier when she was teaching. She said that teachers will appreciate the site. But added that most teachers do not have the time to be creative anymore. They are under tremendous pressure to adhere to Virginia’s Standards of Learning (SOL).

One interesting fact that she pointed out is that since Arlington is a multilingual community many students come from families where English is not their first language. As a result, teaching some subjects, especially Civil War history, can be difficult. We discussed that getting students to “think historically” is difficult if you can’t get them to think about history in general. She explained that teachers use several methods to engage their students. These include auditory, visual, and kinesthetic lesson plans. Of the three, kinesthetic or “hands on” is the most effective. But in the case of students struggling with English, visual literacy projects can be very useful in helping them learn.

For this reason she encouraged me to consider developing a lesson plan that would leverage visual primary sources. She also suggested that a lesson plan that encouraged students to collaborate with other students to review select images, and create their own historical analysis would have several benefits. First, leveraging local historical images would make the subject matter more relevant and interesting. Second, conducting the research and analysis as a team would support the students with weak language skills, and provide them to leverage visual literacy skills they already may have. Third, the core Civil War SOL material could be interwoven in the digital project.

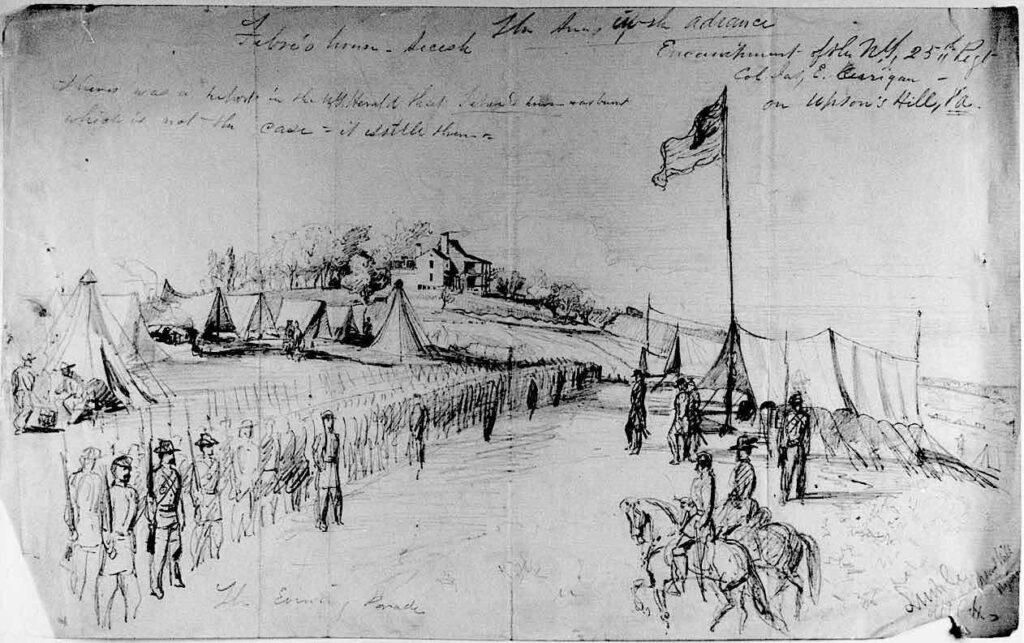

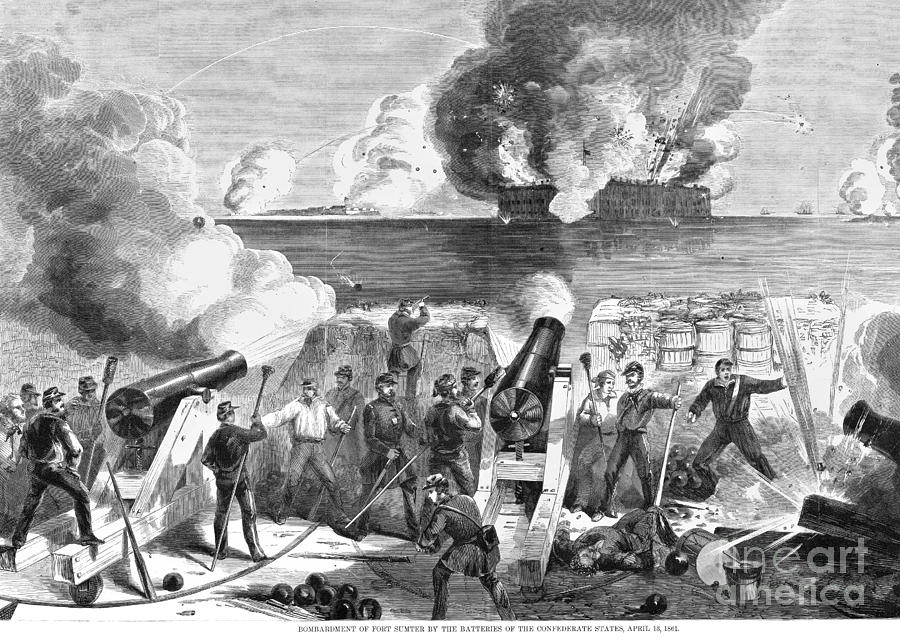

The photograph above of the 8th New York, represents dozens of early war photographs that were taken of Union soldiers in Arlington. “Mapping” includes several already, but I realize that to better support the teaching project I should add at least a dozen more images. This particular image of the New York soldiers is very detailed and provides a variety of topical subject matter that can be easily analyzed. These volunteer New York troops were part of President Lincoln’s original request for 75,000 troops. Overnight, the roughly 2,000 people living in Arlington found themselves hosting over 30,000 Union soldiers. Telling this story of how these troops came from all over the North to Arlington, after the attack on Fort Sumter, would satisfy some of the SOL requirements.

Since these photographs are preserved in high resolution, students can zoom in and observe many details. They can analyze uniforms, weapons, and even how the soldiers were interacting with one another. To help the students analyze this and other images, I intend to follow some of the examples from the readings. The assignments have provided a significant guidance on how to review and analyze historic photographs. I will edit this and other photos and decompose the images into several sections. Each section will provide students to observe certain details, and in the case of the 8th New York, it will included weapons, uniforms, musical instruments, and even the young enslaved African American boy.

The reading assignments have also helped me to start developing a prototype curriculum and lesson plan designed for both 4th and 6th graders. One of the challenges I will face is making sure that my lesson plan aligns with Virginia’s Civil War SOL guide. The other challenge is finding suitable local images that will encourage students to learn more about what happened in their own backyards. The Civil War was well documented and digital collections, such as the Library of Congress, provide teachers and students with a treasure trove of images. Students will learn about the Library of Congress and its primary source collections. My final challenge is to research and review other “visual literacy” lesson plans and adopt best practices to teaching students how to analyze images. These best practices, including teaching students about using primary sources, and “thinking historically.” For example how did early photographers like Mathew Brady use the new medium of to influence public opinions about the war?

In regard to next steps, I will need to evaluate visual literacy templates, and identify lesson plans appropriate for 4th and 6th grade students. The lesson plan must also be based on an inquiry based methodology, that will permit teachers to engage students with all levels of English proficiency. The success of the project will be determined by how easy it is for students to examine an old image, and answer pre-defined historical questions that encourage them to search for details, and even come up with some of their own questions. Finally, the project has to support independent study for those students interested in learning more about their local history. This activity could be promoted by introducing a “webquest” to search other well known historical websites, or even a photo contest by having students visit some of the local historical sites in Arlington. Their photographs could be part of a “before and after” photo essay amd encourage students to create their own digital collections.