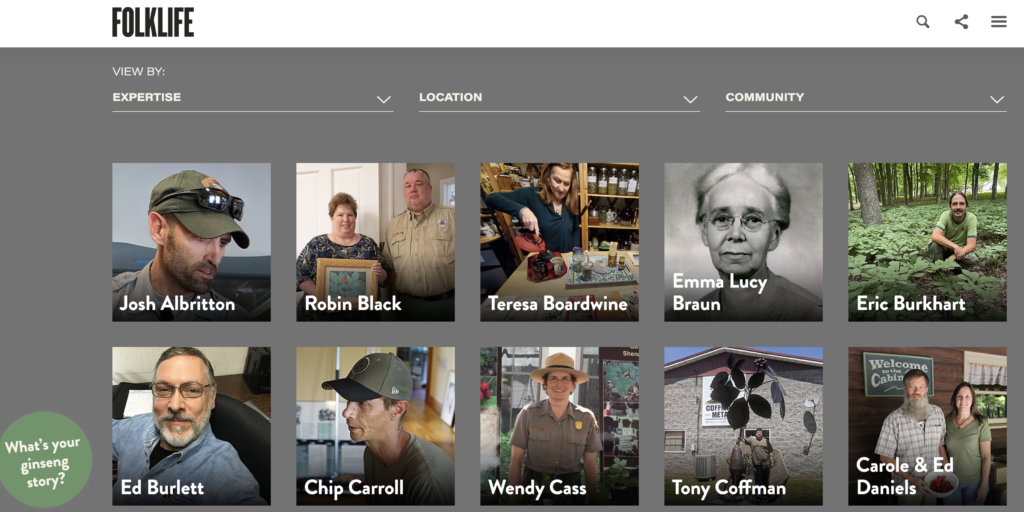

The best part of being an intern is observing and learning. Since you don’t have any responsibility you can stand back and gain a new perspective. It is expected that interns will only be given peripheral assignments, but this gives them the luxury of time to absorb and learn from what others have done. For my internship with the Smithsonian’s Center for Folklife & Cultural Heritage, my job is to assist with the launch of their new website “American Ginseng: Local Knowledge, Global Roots.” Since the project was already well underway there was not much I could offer in the way of web development. However, by arriving at such a late stage in the project my user experience with the site offered some welcomed and neutral perspectives.

Often those close to a project lose their objectivity. They expect everyone to share their passion about the topic and have familiarity with the information presented. In the case of American Ginseng, the site tries to connect local folk knowledge with an overall global perspective. The site does a good job of collecting individual stories, the “Global Roots” is lacking. This could be a problem, especially for visitors that are encouraged to explore the site, but lack a broader understanding of the subject. As a result I recommended that an introductory video, 2-3 minutes would enhance the site’s potential to reach a wider audience. The inclusion of a video would provide the necessary background information to encourage visitors to click on the various stories. Also, overall web analytics confirm that users tend to stay longer on a site when offered the opportunity to watch a video.

The good news is that the idea, so far, has been received well and the production of such a video falls well into my area of expertise. The Smithsonian already has an extensive library of video and still imagery to draw upon to ensure their is sufficient media content for its production. The web team may be hesitant to embrace the idea since the current navigation does not provide a link to multimedia. This is where a shared goal may need to be communicated.

From a learning perspective, trying to engage the project team and get them to accept the necessity of adding the video reminds me of an earlier point in my career. As an assistant producer it was important to present the “facts” to senior staff and gain their acceptance of an idea. Sometimes even let them think that it was their idea. For me adding the video is a no brainer, especially if it will enhance the overall success of the project.

Since it is easy for me to produce such a video, I will need to be sensitive to others who think it might be too complex. They might tend to lean towards saying no due to the bureaucracy. In presenting the case for why it is important I need to stress that an introductory video is an opportunity to leverage the tradition of “oral history” which the Folklife Festival is so well known for. The American Ginseng site was originally designed just for text stories. I understand why, since the submission of “video” would create a nightmare of media quality issues. However, multimedia, especially video, is a clear preference for time conscious visitors. This is evident in web stats and the popularity of YouTube and Instagram.

Finally, as an intern I am having to re-learn how to not only point out a problem but also offer the solution. While I have the luxury to second guess the project’s original goals and objectives, I also have the responsibility to ensure that it succeeds as well. Stay tuned, it will be interesting to see how the outcome.