Overview:

Lying beneath the surface of the popular search engines we use are countless data collections or public databases. These collections carefully gathered and maintained, provide a valuable resource for digital historians. However, not all of these databases are the same. Some are intuitively designed and assist with searches, while others may be full of useful data but are difficult to navigate.

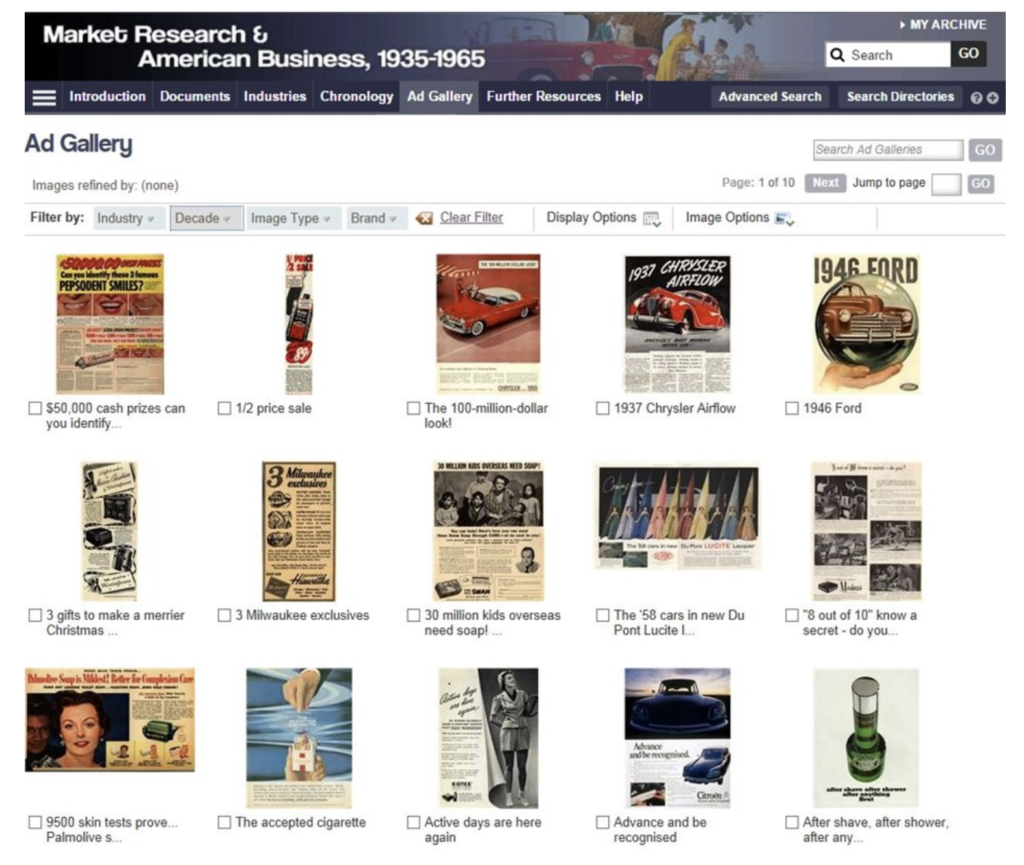

An example of a well thought out collection is the “Market Research and American Business,” 1935-1965 Database. According to site’s introduction page:

“The collection provides a unique insight into the American consumer boom of the mid-20th century through access to the market research reports and supporting documents of Ernest Dichter; the era’s foremost consumer analyst and market research pioneer.”

The collection is also a valuable time capsule by providing access to information on some of America’s best-known brands. It contains thousands of reports commissioned by advertising agencies and global businesses in a booming era for consumerism, ‘Madison Avenue’ advertising and global brands on consumer goods ranging from tobacco and broadcasting to cars and hotels.

But most important the database provides a behind the scenes vantage point of the psychology behind the major American marketing campaigns of the era. The site’s wide variety of available research provides an interesting perspective of America’s consumer culture.

The site provides three ways to search. A basic text search option. An advanced search that includes keywords, text, along with a proximity option. Finally, there is a rather thought out search directory that provides several options including pre-determined lists of keywords, companies, and brands. I found that the search was intuitive and very responsive.

The Market Research and American Business collection provides access to data objects from 1935 – 1965. It includes access to three primary advertising and marketing collections. These include the Hagley Museum and Library; the John W. Hartman Center for Sales, Advertising & Marketing History; and the Advertising Archives. Users are able to download a wide range of research documentation, including studies and proposals, as well as high resolution PDF’s of original published advertisements.

Access:

In regard to “terms of use” and access, the site is primarily for education and research purposes. There are specific sated restrictions, especially since the material concerns some well known brands. There is a detailed FAQ page that provides clear instructions for educators on fair use of the material, including how to cite documents, and what can be downloaded and copied.

In addition, Market Research and American Business has a well written introduction to the collection and provides a very helpful “Page by Page guide” as well as offers users to “Take a Tour.” It goes into sufficient detail for first time users on how to get started, review of resources, and how to conduct searches. Finally, there is an “Editor’s Choice” that provides users with some whimsical postings when Madison Avenue was in its heyday.

Document highlights include topics as:

Why women buy

How to get more people to go to the movies

Attitudes and motivations of the American voter

Cigarette advertising: the untapped possibilities – a creative memorandum on the psychology of smoking

A motivational research study of the Negro market for Esso gasoline, services and related products

Creative research memorandum on the psychology of hot dogs

A creative memorandum on psychological advertising of toys to parents

Cigarette smoking among women

Sexual attitudes in the United Kingdom – today

Marketing Chrysler automobiles in a rapidly changing society

The role of supermarkets in our modern culture

A pilot study on the Bird’s Eye logo

The Advertising Archives Material Types:

Reports

Proposals

Case studies

Surveys

Questionnaires

Correspondence

Memorandums

Pilot Studies

Subjects:

Advertising

Consumerism

History

Psychology

Gender/Women’s Studies

Media

Reviews:

A search of online reviews found several articles that support the author’s conclusion that the Market Research and American Business collection is well organized and supports research efforts to study America’s consumer culture. For example a review form the University of Delaware’s Library, Museums and Press states that the site provides “valuable insights,” and that it is “highly recommended for students at all levels,” and “a unique perspective into the world of buying, selling, and advertising in pre-and post-war America.”

Conclusion:

Market Research and American Business collection sets the bar very high as a database resource. It is purposeful in trying to help researchers get access to the material that they are looking for as quickly as possible . In addition, it goes out of its way in instructing users how to best leverage and the collection assets by utilizing the available search options. Finally, the advertisements and the psychology behind them makes for a compelling story.