The assignment was to take still images and videos of some of the objects in my kitchen. It was part of a lesson module to teach my graduate class about digitization. We take it for granted today, but every time you use your smart phone to take a picture or video you are “digitizing” something. This process captures a significant amount of information and for the most part can easily be shared. However, it becomes self-evident that every image or video is subjective in the eye of the beholder as to the information it conveys.

For example, the image above of the French copper pots does not do justice to the wonderful meals that they have been used to prepare over the years. It also does not convey the tedious work required to shine them up. A cooking video would be more appropriate. So how you capture or digitize an item is really part of the story you want to tell.

According to Melissa Terras, “Digitisation and Digital Resources in the Humanities” (2008) anything that is visible is capable of being digitized. She believes that this process “creates the core content for a digital resource.” Marlene Manoff, in her 2006 abstract “The Materiality of Digital Collections: Theoretical and Historical Perspectives,” points out that every object has “material characteristics.” These characteristics, like size, color, shape, texture, usually can be captured in a digital image. But some characteristics like smell, or sound can not be capture with an image. While sound can be captured with a video, smell-o-vision is still not a reality. As result, the accompanying textual content included with an image plays an important role in establishing the object’s informative value. By supplementing the obvious visual data, more detailed characteristics of an object can be preserved.

Manoff believes that the end result of all this digitization is a “content management” process. A process that has become more personalized as everyone must now learn how to manage their digital collections. In the past, managing the capture of multimedia was dependent upon the manual entry of associated descriptive text or meta data. However, the growing utility of cognitive services like facial recognition, and transcribing, are rapidly automating this process.

Paul Conway, in his 2009 paper “Building Meaning in Digitized Photographs,” points out that more and more cultural heritage organizations are recognizing the need to leverage Image Digital Archives (IDA). He adds that the digitization process is adding value to these organization’s archives by creating “digital” surrogates. But Conway also acknowledges that a digital file of an archived photographic print is still just a representation of the original artifact. Well known institutions like the Library of Congress have become the standard in providing researchers access to a variety of file formats and image resolutions. This provides researchers the ability to determine the level of detail they require.

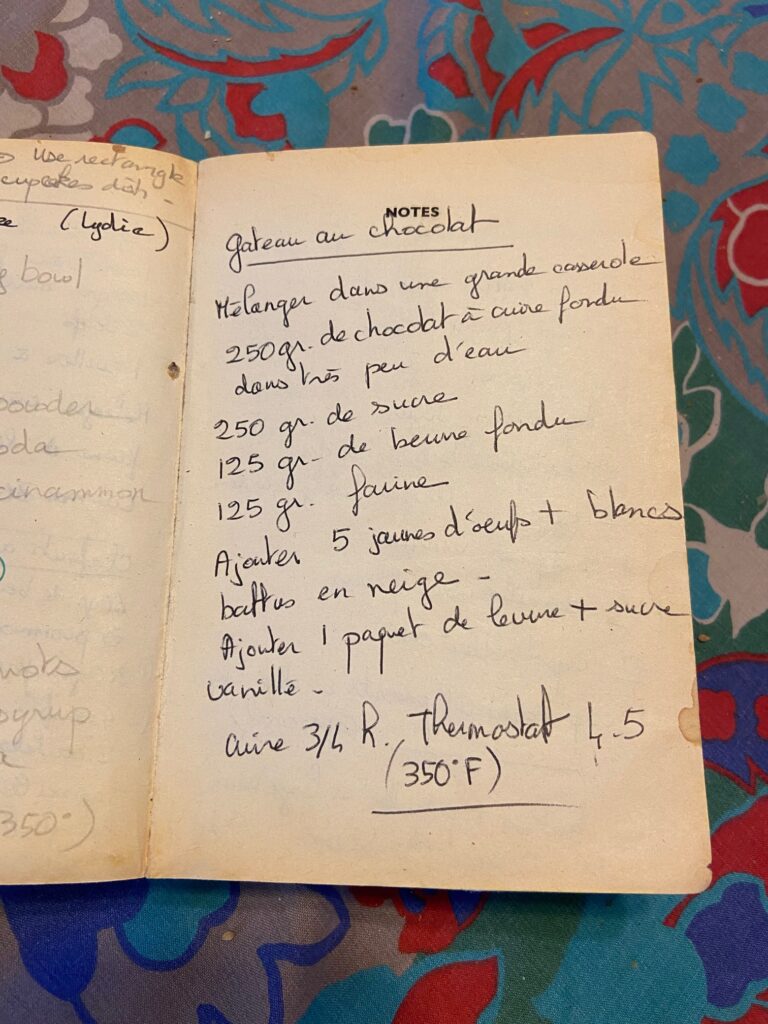

So as a lesson learned the “kitchen digitization” project was useful in determining the broad scope of things that can be digitized, and in what format. One of the assigned items to digitize was a recipe. Shown above is my wife’s family recipe for “Gateau au Chocolat” or chocolate cake. I’m not sure it is a secret, but tasting this cake for the first time probably had something to do with our getting married. But in regard to digitization, just a digital image of the recipe may not have been enough. For those that do not understand French, but are eager to taste this wonderful cake, a translation would be helpful.

Finally, in the field of digital humanities, the creation of these so called “digitized representations” is part of a bigger debate. Are these new surrogates worthy of their own study and should everyone be encouraged to use them as unique objects in their own right?. For me, the issue comes down to accessibility. Having online access to countless numbers of digitized photographs is a tremendous resource. Especially in this time of Covid 19. There is no doubt that in an age of social distancing the need to capture and make public cultural heritage archives is becoming very compelling. Especially if these institutions want to maintain their relevance.