Coding the Past: How AI is Transforming Historical Research

In the age of technology, Artificial Intelligence (AI) is not just revolutionizing industries but also transforming the way we uncover, analyze, and preserve the past. Historical research, often seen as a slow and labor-intensive endeavor, is experiencing a dynamic shift as AI makes its way into the world of archives, data analysis, and the work of historians. Let’s dive into this exciting transformation and explore how AI is becoming a valuable ally in the field of historical research.

1. Digitizing the Past with AI

One of the most significant challenges in historical research has been digitizing centuries-old archives and documents. AI is playing a vital role in this transformation by automating the digitization process. Machine learning algorithms can scan and transcribe handwritten documents, decipher faded texts, and even translate languages, making historical records more accessible than ever.

2. Data Analysis Redefined

Historians have always grappled with vast amounts of data, whether it’s census records, diaries, or newspaper articles. AI-powered data analysis tools can sift through this information, identify patterns, and generate insights at an unprecedented speed. With AI, researchers can now draw connections between disparate pieces of information, uncover hidden narratives, and gain a deeper understanding of historical events.

3. Predictive Analytics in Historical Context

AI doesn’t just help analyze the past but can also make educated guesses about the future based on historical data. Historians can use predictive analytics to forecast social, economic, and political trends, making their research not only informative but also forward-looking.

4. Image and Speech Recognition

AI’s capabilities extend beyond text analysis. It can recognize historical images, paintings, and photographs, helping historians identify subjects, dates, and locations. Speech recognition tools can transcribe audio recordings, unlocking the potential of oral history archives and making it more accessible to researchers.

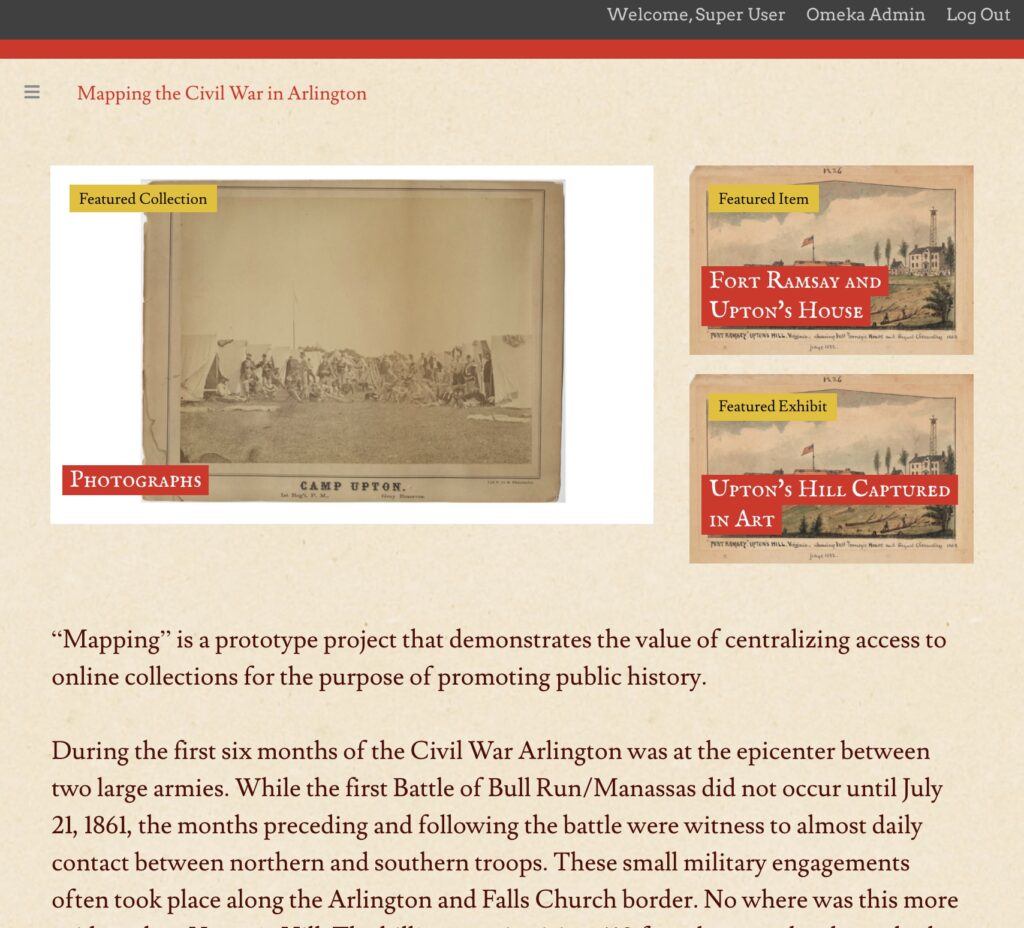

5. Mapping Historical Movements

With AI’s geospatial capabilities, historians can map historical events and movements more accurately. This enables a deeper understanding of the geographical context and spatial relations, adding a valuable dimension to historical research.

6. Unearthing Hidden Stories

AI can discover overlooked or forgotten historical figures and events by analyzing vast amounts of data. These hidden stories add richness to our understanding of the past, showing that there is always more to explore.

7. Real-time Translation

AI can facilitate international collaboration among historians by providing real-time translation during conferences and discussions. This breaks down language barriers and allows for the exchange of ideas on a global scale.

8. Human-AI Collaboration

AI is not here to replace historians but to enhance their work. It can serve as a research assistant, providing historians with the tools and insights they need to focus on the most critical aspects of their research.

In conclusion, the integration of AI in historical research is ushering in a new era of innovation and efficiency. By automating the digitization of archives, offering advanced data analysis, and enabling predictive analytics, AI is empowering historians to uncover deeper insights and share their findings more effectively. This synergy between human intellect and artificial intelligence promises to make history more engaging, accessible, and relevant than ever before. Embrace the future of historical research, where the past and the future coexist, thanks to AI.

AI and Storytelling

Both for “Insights” and creating content

historical figures coming to life (talking to historical figures), image/facial recognition

Next, an exciting video that demonstrates fascinating possibilities for digital storytellers. A YouTube channel, Views of an AI, recently published “Blade Runner 1929”, a concise video that combines the classic 1982 film with a group of 1920s movies and styles focused on Fritz Lang’s work. It’s just over three minutes long