At the end, over 160 years of history came tumbling down in a matter of seconds. Despite a heartfelt and very public effort to save the Febrey Estate, the owners were permitted to proceed with its demolition. Historic preservationists vainly attempted to leverage social media, including Facebook, and a Moveon.org petition, to mobilize local residents to challenge Arlington County’s board to preserve the property. However, it was too little and too late. Buried among the ruble is suspected Civil War soldier graffiti, and other 19th century artifacts there were unable to be saved or documented.

But in regard to advancements in technology and their impact on public history, the lessons learned from the “Save Febrey” campaign are worth noting. First, there is no doubt that social media is a game changer in getting the word out and creating awareness. The one victory in the Save Febrey effort was getting Arlington County’s Historical Affairs and Landmark Review Board (HALRB) to recommend that the Febrey Estate be designated historic. Unfortunately Arlington County’s board did not act fast enough to confirm the status. As a result a permit to destroy the house was issued prior to a formal vote.

A second and more important lesson, is the future role that technology is going to play in what author Barbara Heinisch, describes in her 2020 article “Citizen Humanities as a Fusion of Digital and Public Humanities?” Ms. Heinisch points out that this fusion will permit citizens to be more engaged and contribute to policy and democratic processes. The failure to save the Febrey estate is in part due to the general lack of awareness of the site’s history. Unfortunately the ability to uncover the historic forensics was a monumental task. Only as a last minute, and desperate attempt to scour the digital repositories did some interesting public stories surface. One positive result of the experience is that many of these stories can now be shared.

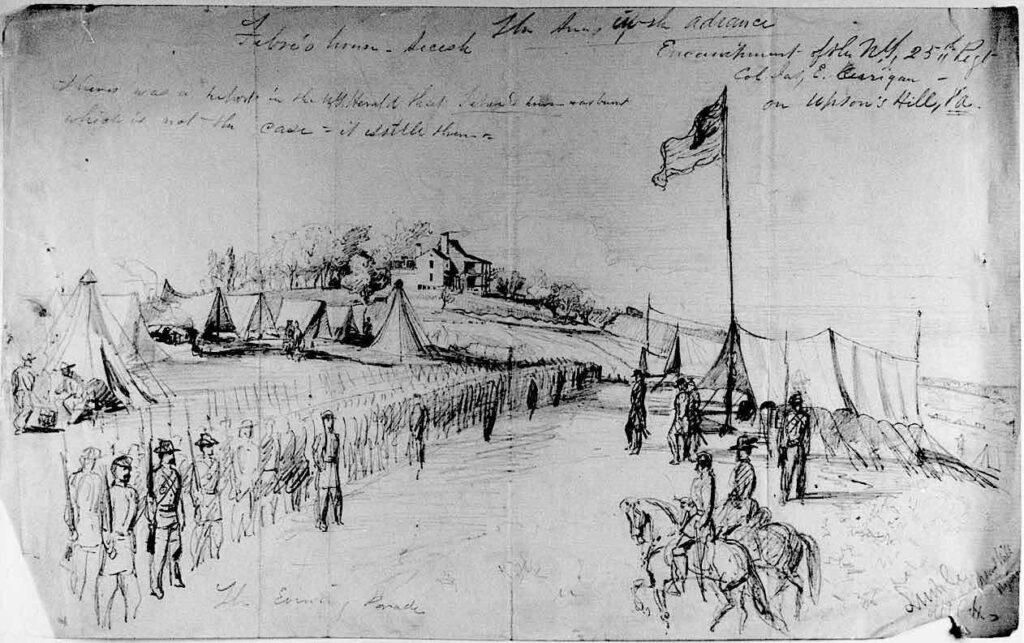

It was clear from the recent historic preservation effort, that a few people can not emulate decades of historical research. But the one area that technology can help is in the “wisdom of the crowds.” In the case of the Febrey Estate the discovery of a Civil War drawing for Frank Leslie’s Illustrated publication confirmed that a portion of the house date back to the 1850s,

While the drawing has been there for over 160 years, it took the action of a local resident to bring it to everyone’s attention. The drawing sparked an interesting debate, but the architectural proof and visualization was irrefutable. What was compelling is that Lumley documented the name of the family, Febrey, in the drawing’s notes. Barbara Heinisch asserts that technology’s influence on citizen humanities will lead to “mutual exchange and knowledge co-production.” This digital collaboration and engagement is where technology will have the most immediate impact.

A third and final lesson learned, is the need for local governments and historical organizations, to invest in online digital collection platforms. The demolition of the Febrey house, without any defined plan to curate or document the historic structure is tragic. The cost of these online collection platforms have been drastically reduced. The Omeka open source platform is a perfect example of how accessible they are right now. But the cost of full-time historic research staff is still an obstacle. Arlington County staff were limited in their ability to collect and curate the rich historic potential that the estate represented. The Febrey example demonstrates that if public history programs are going to succeed they will need to leverage public participation. Large-scale crowdsourcing projects are now manageable and their impact is worth the effort. Labor intensive activities such as tagging, transcribing or annotating research data, can now be supported by vetted volunteers. According to Ms. Heinisch, this could also “encompass forms of participatory (action) research or co-creation, such as initiatives in which the community has the lead or shares stronger responsibility with academics or co-develops research questions, research designs or project management.”

The local impact of the destruction of the Febrey house is still to be determined. But the public reaction so far has been one of dismay and disappointment in their county’s government to act swiftly enough to preserve such a historic site. One thing for sure is that in the historic preservation movement, advancements in information technology will continue to have a significant impact on citizen humanities and public history. For the citizens of Arlington it is hoped that the demolition of the Febrey estate will serve as a reminder that it takes a “village” and the “wisdom” of the crowd to preserve and protect its heritage.