At a public forum regarding the Civil War in Arlington, a local historian claimed that nothing of “importance” happened at a particular location. A location that is being considered for a major preservation project. It was a simple statement. Since this person is considered an expert on local history his “interpretation” carries some weight with the Arlington community. However, it was obvious that his observation was not based on fact, but rather a lack of awareness or acceptance of a growing body of new evidence. A body of evidence that includes publicly accessible primary source documentation that actually refutes his claim.

This episode made me think about public history and the role of local historians. It especially made me go back and review Ronald Grele’s article, “Whose Public? Whose History? What is the Goal of a Public Historian? (1981). Now over 40 years old, Grele’s work still provides one of the best descriptions of “public history.” He lays out a strong frame work for understanding the evolution of historians, from their academic origins, to local historians, and public historians. What he was not able to foresee, was the next evolution, where audiences can now participate in the interpretation process. Something that I would define as “social history” or social media history.

Social media offers a new way for historians to engage with their audiences, whether it be primary or secondary. Public history is no longer limited by small, in person venues, like a class room or library. Instead public historians can reach thousands in an instant. Nor do authors have to wait years to publish their work. The internet and social media is dramatically changing our concept of public history.

For my project “Mapping the Civil War in Arlington” I conducted research on my intended primary and secondary audiences. My first interview was with Tom Dickinson, a member of the board for the Arlington Historical Society (AHS). Since the mid 1950s the AHS has been a significant force in shaping, and defining Arlington history. It has been publishing an annual magazine that provides a venue for local historians to present their research and findings. Members of the AHS would be a primary audience. They would be interested in learning more about Civil War history and how it is related to Arlington. The project would also benefit from AHS members and other local historians contributing and confirming historical accounts and sources.

Mapping the Civil War may be considered disruptive to some primary audiences, since it challenges long held beliefs within the AHS that nothing of military significance happened in Arlington county. While AHS has published several articles about small skirmishes, and the impact of northern troops occupying the county, there never was a wider interpretation of the role Arlington played in the Union victory. Arlington’s Civil War history has long been overshadowed by Southern General Robert E. Lee and the “Lost Cause” narrative that portrays him and other Confederate leaders as noble but conflict figures. In fact for decades, the county’s logo is a representation of Arlington House, Lee’s former home. Last year the county government announced that it was going to change the logo, as well as continue to review school and street names that honor Confederate leaders.

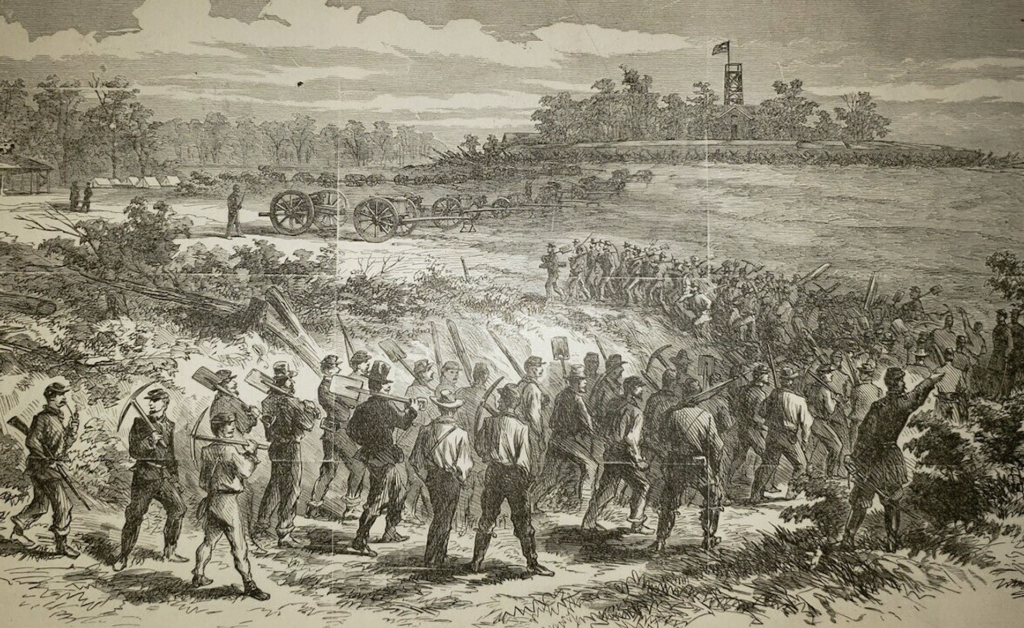

My second interview was with a Civil War history buff and living history reenactor. He just happened to be my brother Tom Vaselopulos. Tom lives in Lexington, Kentucky, and represents a wider and potential secondary audience of history enthusiasts who conduct online research. In my brother’s case, specific his interest is in the history of the 79th New York Volunteers, or better known as the “Highlanders.” His reenactment group portrays this particular unit that was made up of Scottish immigrants from New York City. The 79th New York were part of the first wave of Union troops that arrived in Arlington early in the war. They helped build Fort Corcoran which was located in Rosslyn overlooking the Potomac river.

Mapping the Civil War will attract a lot of interest from secondary audiences since it will provide online access to a wide collection of Union and Confederate regimental histories. Tom and other Civil War buffs would be very interested in learning more about the role of individual regiments and their experiences in Arlington. These histories will also support and provide irrefutable evidence of the wider scope of local military activities in Arlington. For example, elementary students will be able to learn about what happened in their own backyards. One of the project’s goal is to allow audiences to participate and contribute to the collection process. Civil War records are quite extensive. It will require a significant amount of collaboration/co-creation, between audiences and participating local historians, to map this history. People of all ages and backgrounds would be able to participate.

In regard to the impact of the audience research on my project, I would like to quote from Ronald Grele’s article.

“The current growth of public history and the debate over the definition of the historical profession has taken place within the context of an ironic situation. The study of history is in almost total collapse in the academy, while the popularity of history with the public is growing everywhere”.

In order for Mapping the Civil War to succeed, it has to provide the means for a wide range of participation and engagement to ensure that the historical collection and interpretation process is objective. This means that the goals of “Mapping” should not be to narrowly define the historical interpretation at the start of the project. Rather the goal should be to strive for transparency. In order to minimize subjectivity, the project needs to establish well-defined and agreed upon criteria that will determine and rank the historic value of the intended collection records. This ranking process will be dynamic and leverage social media to permit audiences to comment and post their preferences.

As Grele observed, the popularity of history is growing. Advances in social media and online collection technologies are evolving. As a result we are witnessing the emergence of the next generation of “historians.” For communities like Arlington, history may be local, but it is also impacted by broader audiences who are interested and may want to contribute. Mapping the Civil War can benefit from the “wisdom” of this crowd and these new social historians.