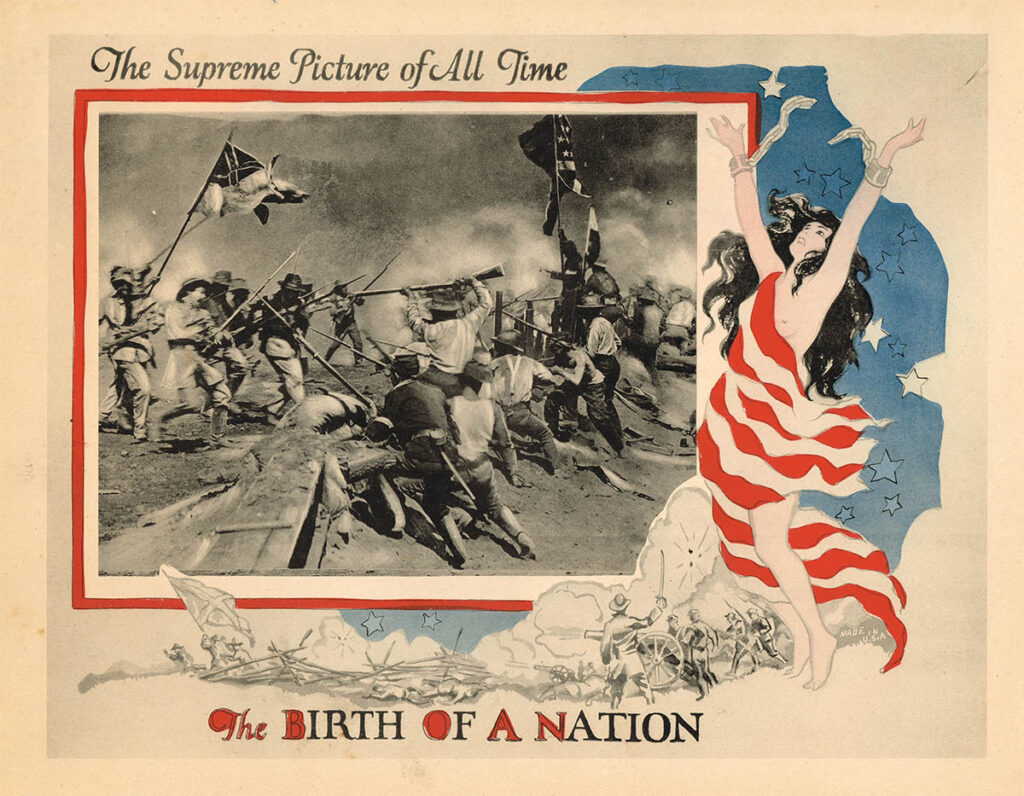

It has been over a century since D.W. Griffith’s controversial film, The Birth of a Nation (1915) made its cinematic debut. The movie about the origin of the Ku Klux Klan (KKK), was a huge success at the box office and it played an important role in the development of the American film industry. But it also represents a significant problem with Hollywood and history. Since the advent of “moving pictures” audiences have gone to theaters to be entertained and not necessarily to be taught history. In fact, in the art of filmmaking, historical accuracy is usually left on the editing floor. That is why we must approach the use of films as educational resources carefully.

The Birth of a Nation represents a major turning point in the evolution of “public history.” Until the film’s release in 1915, the history of the Civil War was confined to academia and the publishing of autobiographies and biographies of historic personalities. The timing of the movie is significant, since the war had been over for 50 years and many of the northern and southern veterans were starting to pass away.

From a 21st century vantage point it is easy for us today to be critical of the 106 year old film. Yes, it significantly distorted historical fact, it was racist, and unfortunately supported the South’s “Lost Cause” narrative. But for audiences (at least white audiences) in 1915 the film was compelling and and racial integration was still a work in progress.

Since the release of The Birth of a Nation, Hollywood has been telling and retelling the story of the American Civil War. There are dozens of popular Civil War movies (https://www.imdb.com/list/ls000038854/), including the 1939 epic Gone with the Wind, the 1951 adaptation of The Red Badge of Courage, Glory 1989, Gettysburg 1993, and Lincoln 2012. The problem for most audiences, is they are easily convinced that what they see on the screen is historically accurate and often don’t bother to check the facts. For those teaching history this presents both a problem and opportunity to use these films to point out, and have students reflect on, these historical inaccuracies.

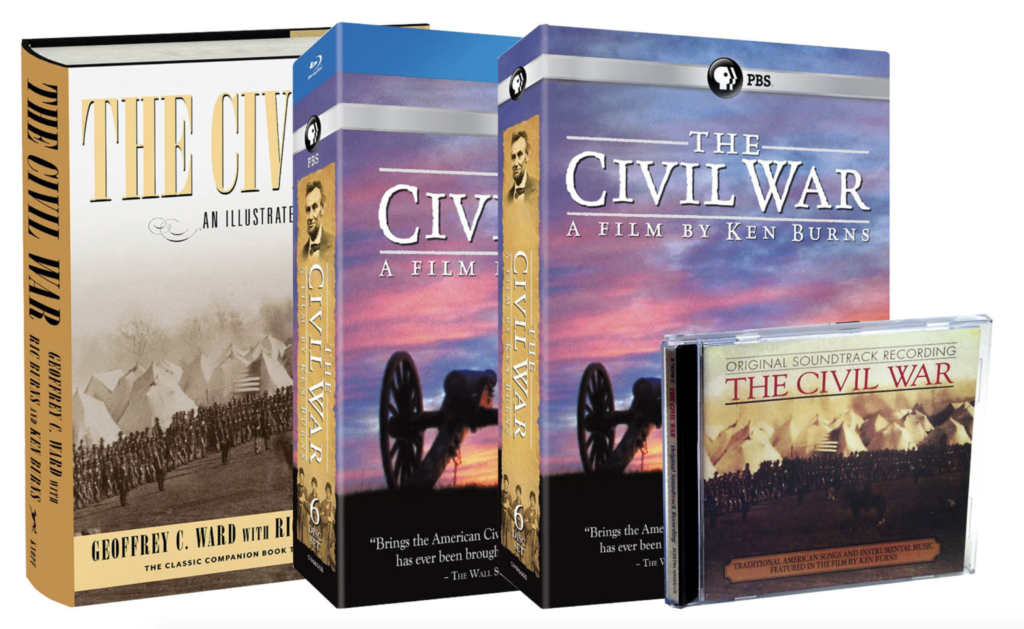

In regard to digital storytelling, we now live in a world that online media technologies permit anyone to become their own D.W. Griffith or even a Ken Burns. His popular 1990s historical documentary The Civil War, recently celebrated its 30th anniversary. For historians, Ken Burns is the gold standard for visualizing history. In fact Apple’s IMovie has a special effect called “The Ken Burns Effect” that allows users to replicate the motion of the camera panning over old photographs.

But even 30 years later Burn’s historical interpretation is being criticized for not questioning southern historians like Shelby Foote, and their persistence in advocating the “Lost Cause.” This is a stern warning for anyone that wants to enter into the realm of scholarly storytelling. The popularity of Social Media, and the ease to create visual content, provides students with some creative learning opportunities. The very nature of media production and editing, forces students to be selective and stay focused on arguing the major themes or historic interpretations they want to support. But unlike The Birth of the Nation, over a hundred years ago, today’s media also permits audiences to react to historical thinking almost immediately. This forces film producers, amateurs and professionals alike, to be on their guard and do the historic research.

Good storytelling, at the expense of bad history will no longer be tolerated, or at a minimum ignored. The “long tail” of the digital humanities world will eventually expose or at the very least embarrass would be “Ken Burns” of the future. Hollywood is finally taking note that “historically thinking” is here to stay. Historic films will continue to be popular, and hopefully continue to be more accurate.