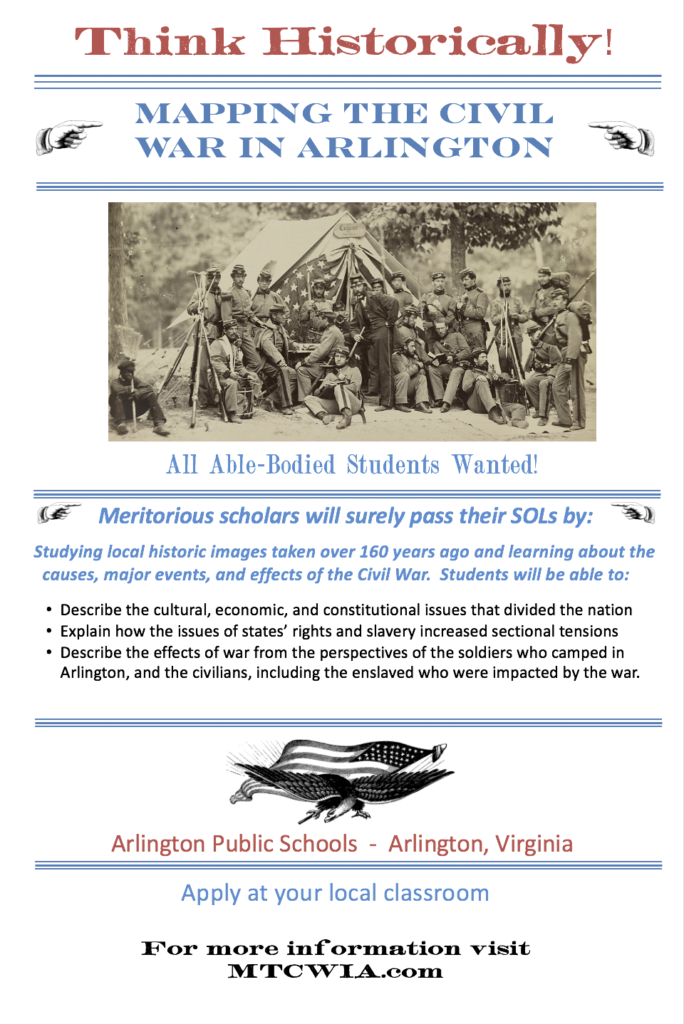

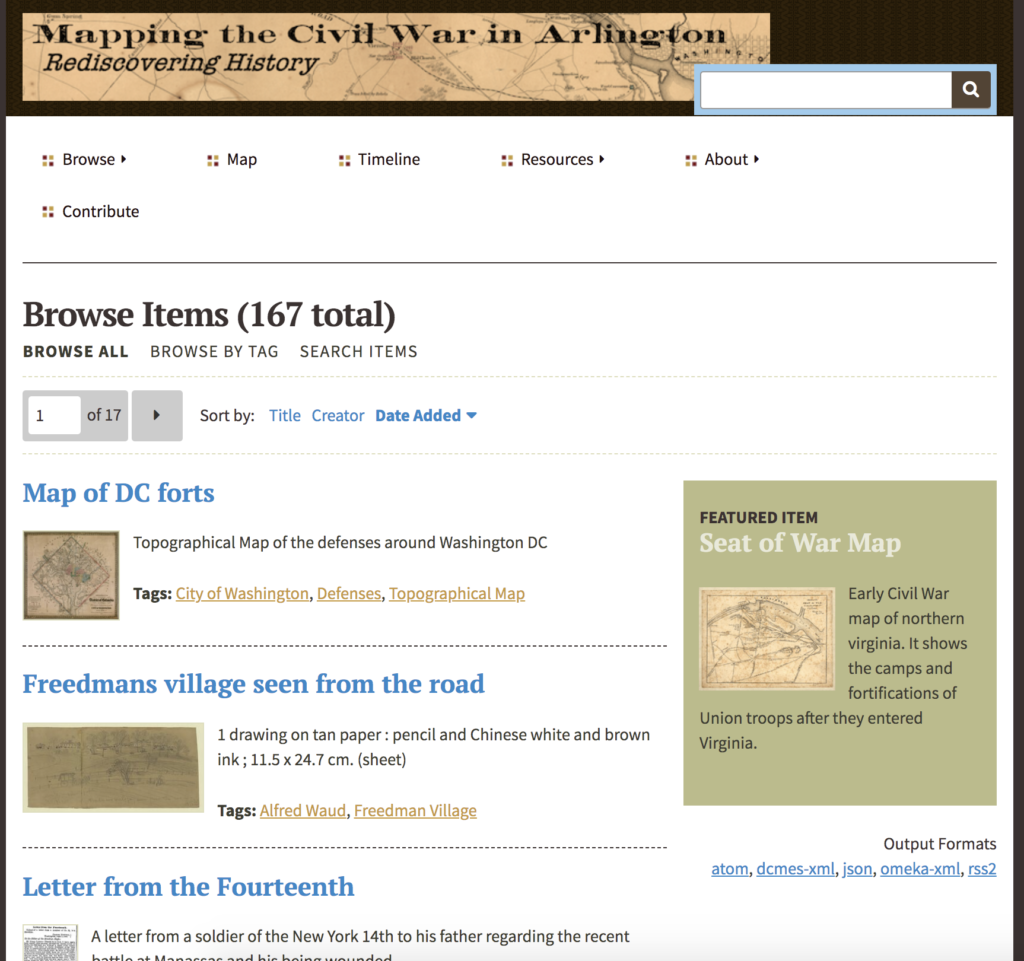

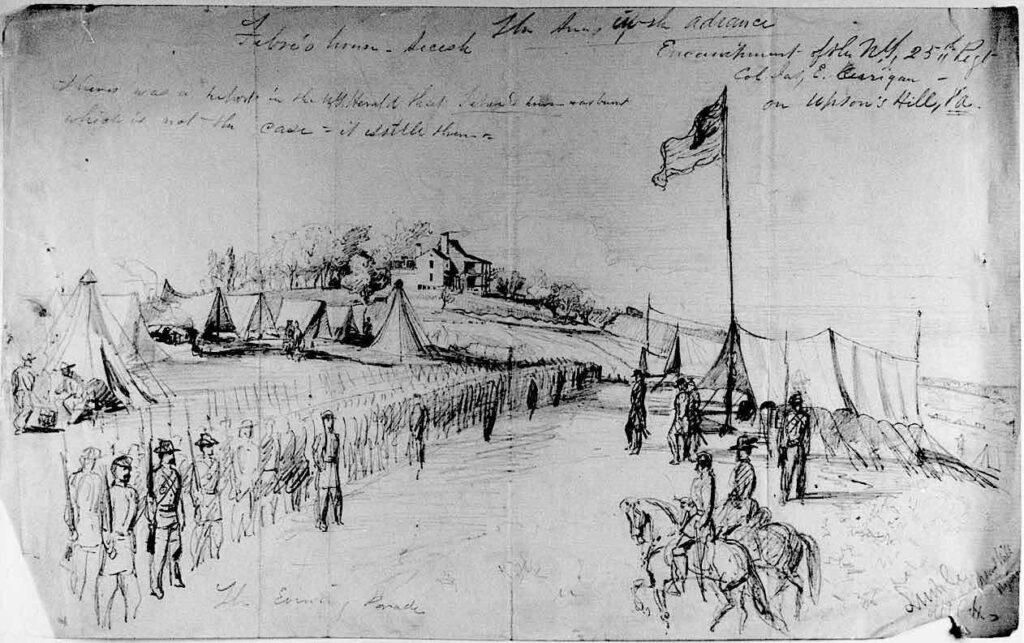

There are only a few weeks left for class and the assignment this week is to report on the current state of our projects. As an overview I am leveraging an online digital collection I created for my last class, Mapping the Civil War in Arlington. The purpose of the project is to use an actual local historical event, the Ball’s Crossroads Skirmish, to draw students into a Civil War lesson plan. The goal is to have students “think historically” by analyzing photographs of Union soldiers from the 23rd New York Regiment, that fought in the skirmish. In addition the students will read newspaper articles, diaries, and regimental history that describe the historic event.

I initially wanted to create a Civil War lesson plan for Arlington 4th graders, but after speaking with a retired teacher, I decided to focus on 6th graders instead. This decision was based on several factors, first, the Virginia Standards of Learning (SOL) for 6th graders was more flexible, and second, they would have better writing skills. Not only will the students have the opportunity to analyze the photos, but also be encouraged to write their own news article, pretend to be a soldier writing a letter back home, or write an essay for the Arlington Historical Society.

For my next steps I am finalizing several deliverables. These include:

- Student lesson plan webpage on my site with instructions and links to the necessary resource material, including videos, and primary sources.

- Photo analysis worksheet that includes specific questions to help the students analyze their selected images.

- Historic background resources, including primary sources like newspaper articles, diaries, and regimental histories. Also, there will be several videos that a provide additional historic context.

- Teacher’s guide, with necessary resource links, assist with instructing the students and explain their assignments. The teachers will have an opportunity to leverage several background resources to customize the lesson plan based on what they believe to be the higher learning concept objectives.

In regard to challenges that I have encountered, there have been several. First, based on what I learned from my interview with the retired teacher, the timing of the lesson plan has to be flexible. For example, it needs to be short enough, where the photo analysis research and group assignments can be completed in a single class period. However, the optional written assignments can be completed as homework over a few days. The topic of the lesson plan also has to clearly align with the SOL material that has to be covered. Finally, the scope of the lesson plan and age appropriateness, requires some thoughtfulness in pre-selecting what primary source material the students will review.

To ensure that my lesson plan will overcome these challenges, I plan on having the retired teacher review the deliverables. It is my intention to design the lesson plan with as much flexibility as possible. I recognize if the plan is too complicated or takes too much time it will not be used. I hope that there will be sufficient time to review her comments and apply the necessary changes. Stay tuned and let’s see what progress I can make during the next week.