In Virginia, 4th grade is when students get their first introduction to the American Civil War. For teachers there are many resources and guides to help them navigate through the complex and difficult themes associated with the conflict. However, in Arlington, there have been recent historical discoveries that makes the war even more relevant for students.

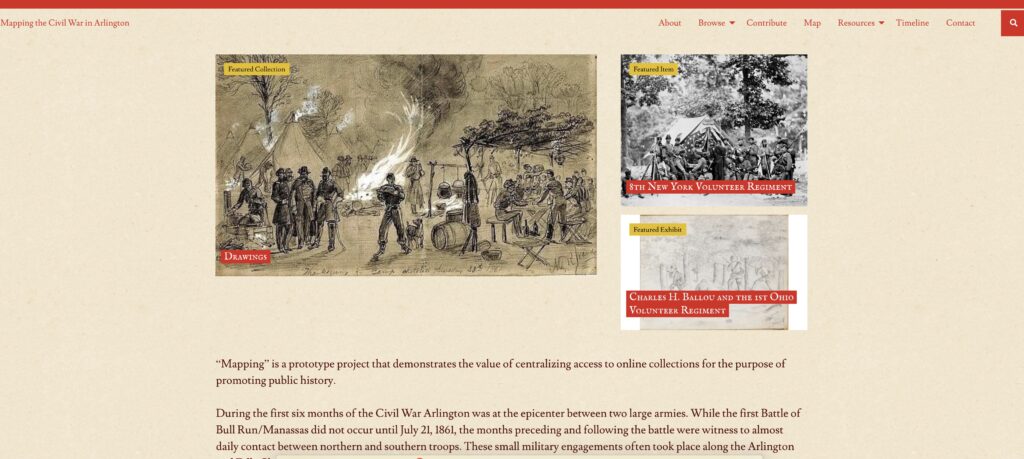

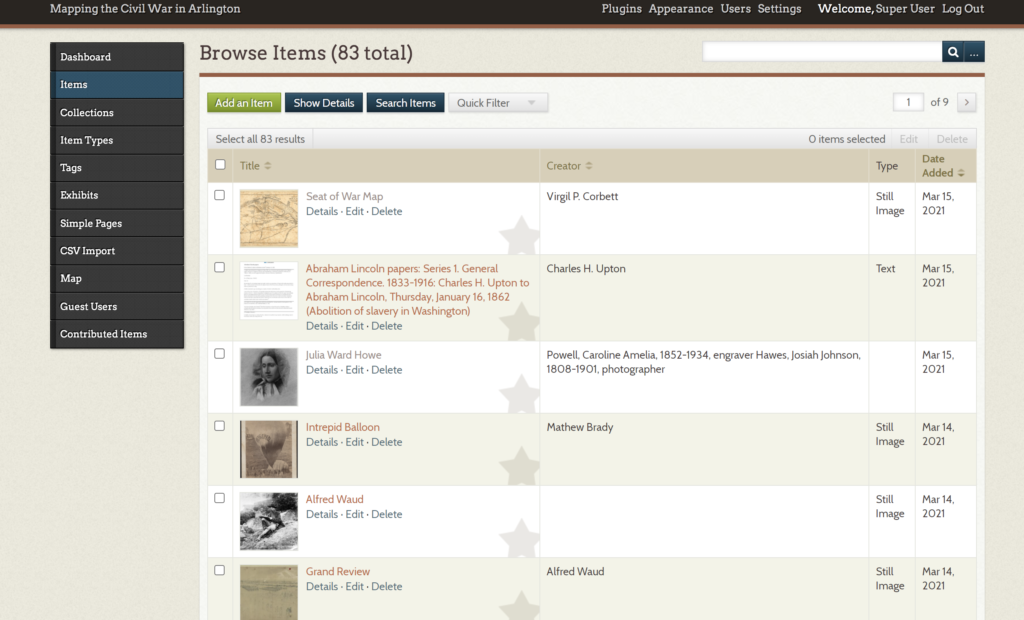

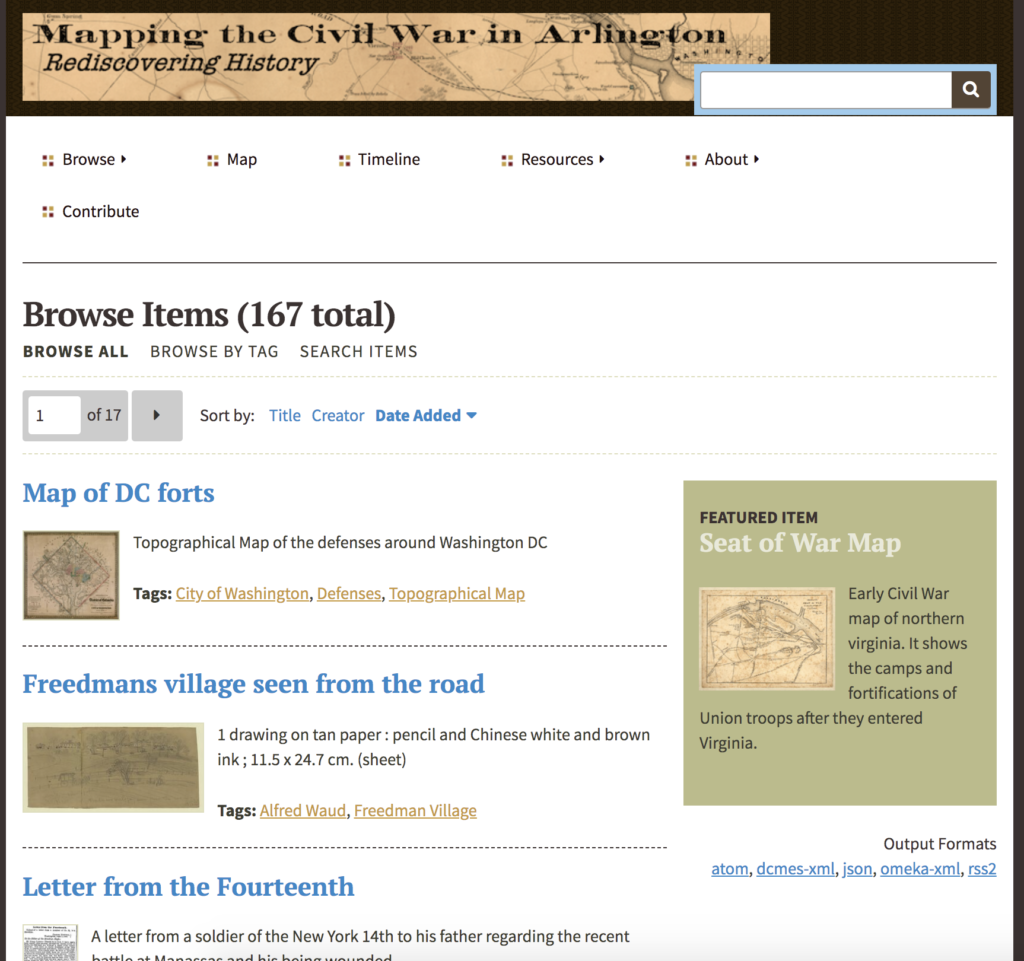

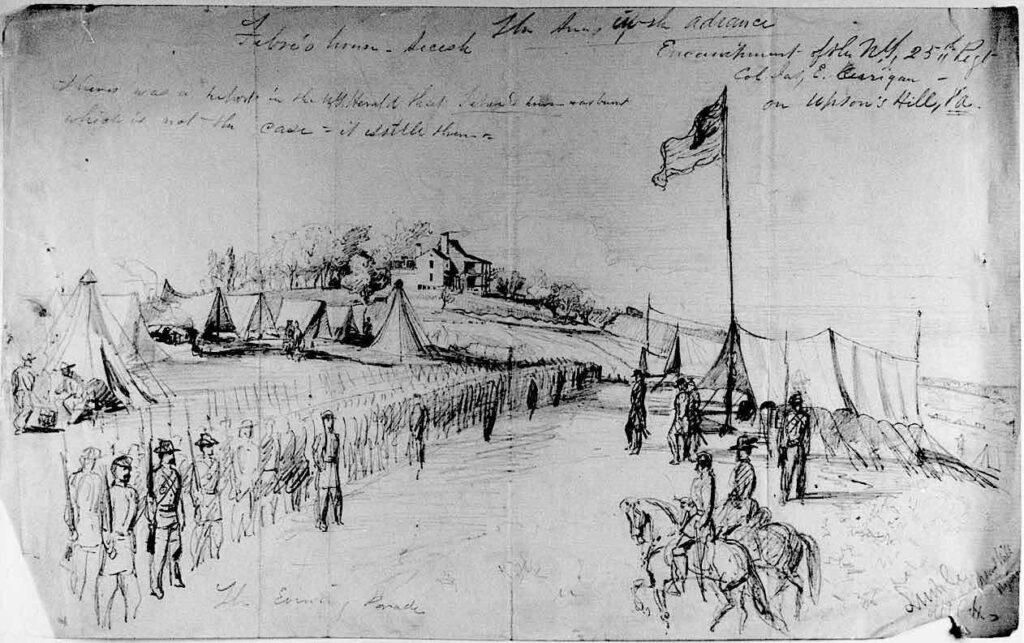

As part of a historic preservation campaign to save the Febrey Estate located on Upton’s Hill, researchers “rediscovered” the property’s connection to the Civil War. As a result, an online collection of primary resources are now available for teachers and students to review and analyze.

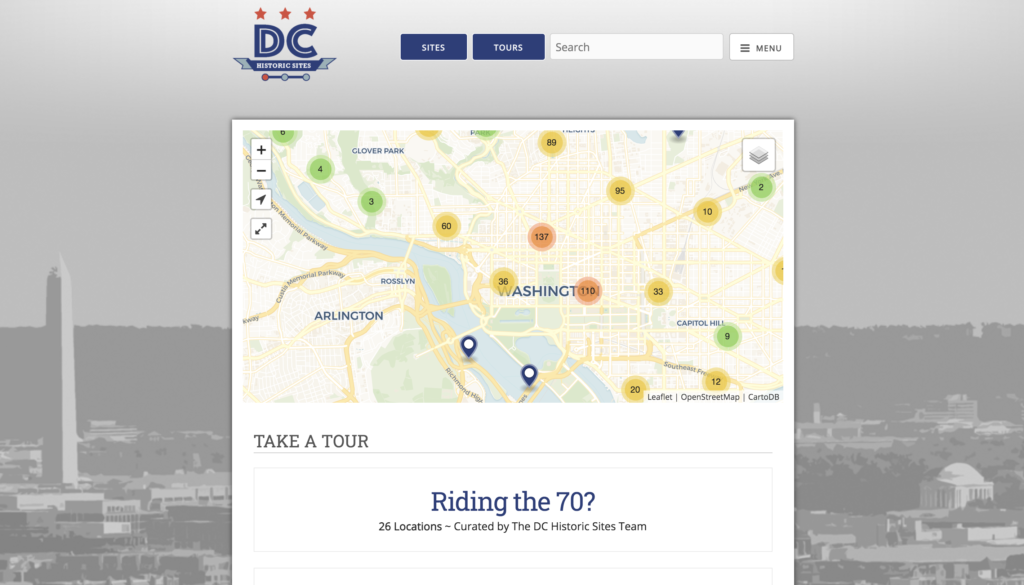

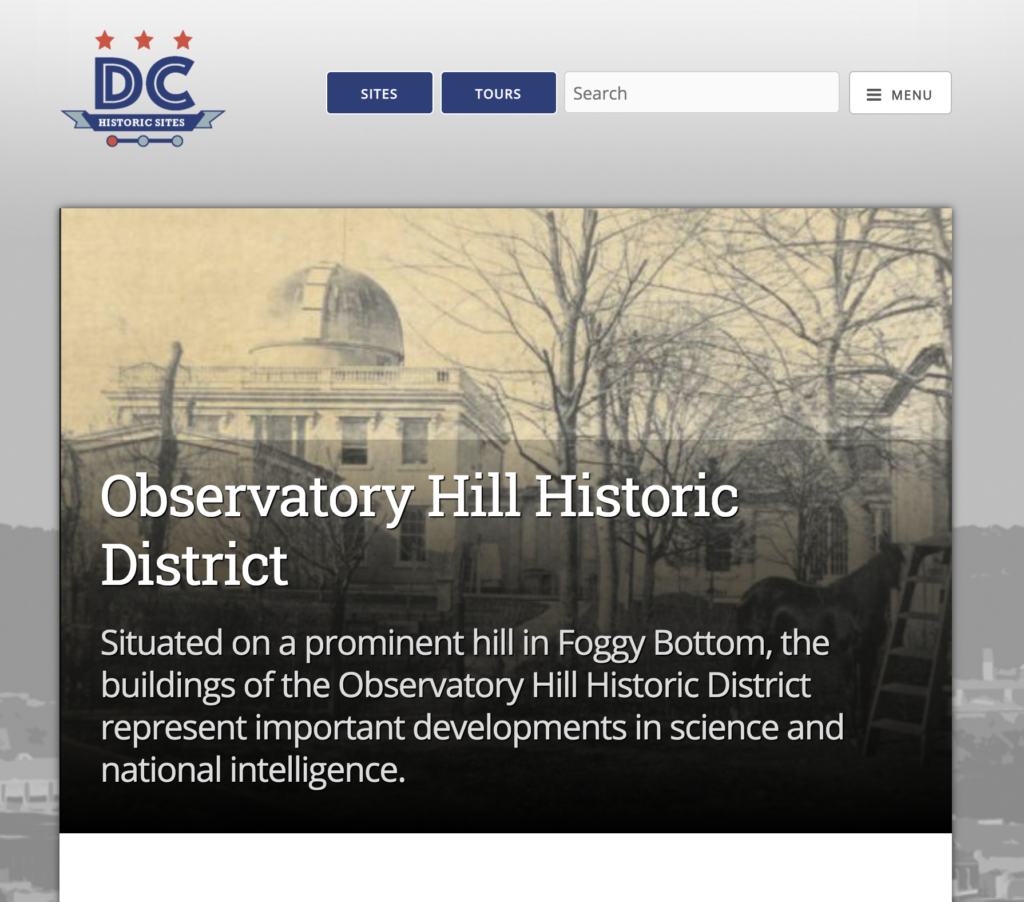

The project called “Mapping the Civil War in Arlington” provides students with a asynchronous digital learning opportunity. Using the site’s map, students can explore a multitude of primary sources, including historic photographs, letters, official records, books, and diaries.

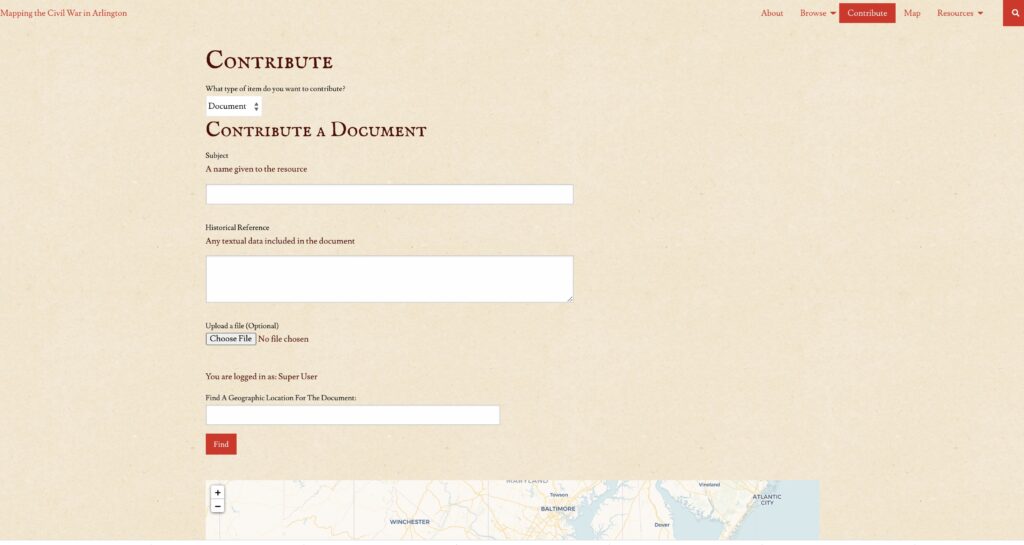

The site also encourages teachers and students to collaborate and make contributions to the site if they discover an unknown primary source. The following list of competency questions have been generated to assist Arlington County elementary teachers develop their own Civil War lesson plans that focus on local history. The goal is to make the Civil War more relevant to Arlington’s students.

Geography

1) What are some of the unique geographical features of Arlington County that made it so strategic during the war? (Arlington Heights, hills, valleys, Potomac river).

2) Compare and contrast a modern map with one from 1861. What roads existed then? What bridges existed then? What about transportation like canals or railroads? How long did it take people to travel a mile compared to today?

3) What cities or towns existed back then? What was Arlington’s relationship with Georgetown, Alexandria or Falls Church?

4) When was the Alexandria, Loudon, and Hampshire railroad built and why was it so important during the war? What battle took place on the railroad early in the war (Battle of Vienna)?

Politics

1) What was the Retrocession of 1846 and what were the root causes? What was slavery’s role in the return of Alexandria to Virginia? What impact did the 1862 Emancipation Proclamation have on Arlington?

2) Who were the radical republicans and why were so many people living in Arlington at the time considered Unionists?

3) Why did President Abraham Lincoln wait until May 24, 1861 until sending Union troops into Northern Virginia?

4) What did the Virginia vote on May 23, 1861 (Referendum on the Ratification of Succession) decide?

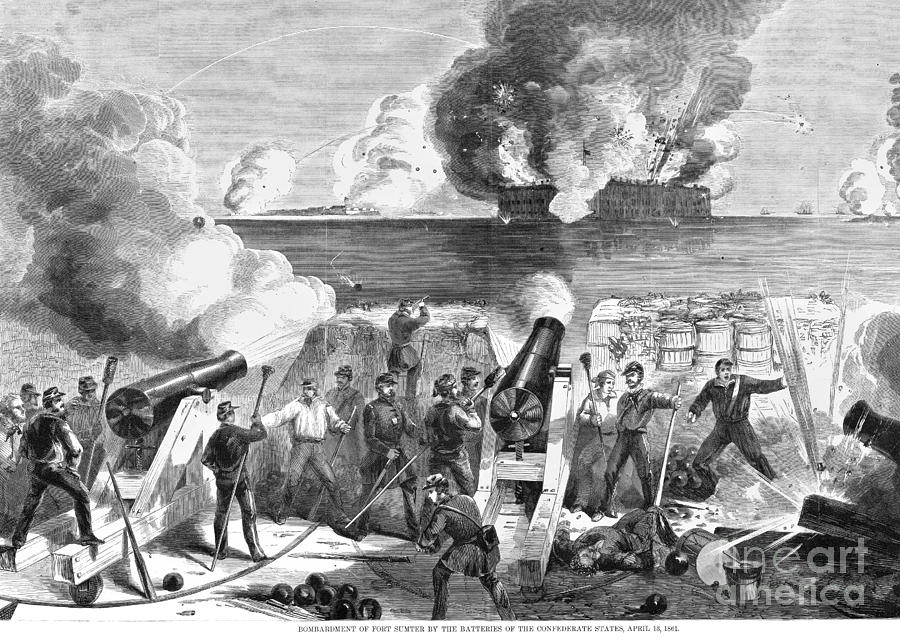

Civil War

1) What were some of the strategic objectives of the Union Army in occupying Arlington? (Construction of forts, protecting bridges, establishing camps)

2)Identify some of the fort and camp locations from early 1861, what is located there today?

3) What is the closest camp or fort to where you live in Arlington?

4) Who were some of the famous Civil War personalities that spent time in or around Arlington during the early war? (Robert E. Lee, President Lincoln, George B. McClellan, James Longstreet, Jeb Stuart, and Irvin McDowell?

5) What military technology innovations were first tested in Arlington? (the use of gas filled balloons for aerial observations, the use of rubberized telegraph wire to link fortifications)

Impact of the war on Arlington

1) What was life like for the 2,000 people living in Arlington during the war?

2) How did all of the camps and fortifications impact the countryside? (destruction of Arlington forests)

3) Were there any military engagements that took place in Arlington? (Arlington Mill Skirmish, Ball’s Crossroads Skirmish)

4) Where did the Union soldiers come from? Which northern states sent the most troops? What did they say about Arlington and their experiences while staying there?

5) How did soldiers drill and live in camp?

6) What are some of the types of Civil War artifacts that have been found in Arlington?

7) What was the Army of the Potomac and why was it important in the ultimate Union victory?

For Arlington’s 4th grade students “Mapping” brings the Civil War to their backyard. Long forgotten, many primary resources are being rediscovered and they are helping both teachers and students alike to think historically. By “localizing” the Civil War students will be more interested in learning not only about what happened down the street, but why.